Here was the big question, the one underneath the pot-leaf name tags and the thousand-deep crowd of women shouting mantras in the opera house and the slight smell of weed in our parkas and Melissa Etheridge’s ombré sunglasses and the après-ski-hot girls with angled haircuts and the shy 55-year-olds furiously writing down dosage information for their parents’ end-of-life care and the giggling grandmas from Oklahoma sharing their first vape: Of the existing billion-dollar industries, women are in control of none of them. Could legal cannabis be the first?

As women, weed, and control make up three of my top five interests, I had flown to Denver for the annual Women Grow conference to find out.

“Isn’t this beautiful?” shouted Sherry Glaser, an actress and political activist, gesturing from the stage towards the rapt gathering of women in the large, grand, red-velveted auditorium in Denver’s downtown. “Aren’t we beautiful? Where are you from? I hear Toronto! I hear Puerto Rico! I’m from the earth! From my mother’s womb!”

In fairytale cadence, Glaser told us about how she opened the first-ever dispensary in Mendocino, California—a legendary weed town that now makes up one of the three points of the state’s “Emerald Triangle,” which is a 10,000-square-mile stretch of forest that attracts seasonal “trimmigrants” and is said to produce more of that Dank Sticky What Have You than any comparably sized region in the world.

In 2005, Glaser was arrested on the steps of the California State Capitol while toplessly protesting Arnold Schwarzenegger with the organization Breasts Not Bombs. On March 2014, Glaser found herself in a more unexpected confrontation: she, along with the rest of the Love In It Cooperative, woke up to the DEA pounding down their doors. Everyone was handcuffed, everything was ransacked, eight people went to jail. “They charged me with intent to sell. Sure! I had a store!” she shouted, onstage.

(At that time, it was illegal to profit from marijuana in California; collectives and cooperatives were prohibited from taking in income past what they needed to cover their expenses. This changed in September 2015, with a bill package that brought much more of the industry aboveboard; a ballot measure in November will likely change regulations again, making recreational marijuana legal in the state. For anyone in this business, staying abreast of the shifting layers of local, state, and federal liability is essential and daunting: finance itself is a quagmire with the industry cash-only, federally illegal, but taxed at an especially high rate by the IRS.)

Glaser talked about PTRD, or post-traumatic raid disorder—a joke that seemed flippant and slightly offensive to me until the women around me started murmuring about the risks they ran of arrest, asset seizure, having their children taken away. (If a parent is detained for a reason related to the marijuana industry, Child Protective Services in Mendocino is called automatically.) But Glaser triumphed over her PTRD, re-opening the collective in 2014, she said. The crowd went apeshit. Glaser closed her talk out with an exercise called the “Boom Chakra Laka,” enthusiastically grabbing her “root chakra,” which is, I guess, the crotch.

Everyone is so fuckin happy, I tapped out hastily on my phone, as hundreds of women around me air-grinded, affirming their simultaneous holistic existence as the Boom Chakra Laka slid into whistles and wild applause. Everyone like YAS TIME 2 MAKE MONEY W MY SISTERS. This is the safest space I’ve ever been in my life.

Women Grow, an organization that connects, supports and promotes women in the weed biz, is ballooning as fast as the industry it’s tied to. Last year, the Women Grow conference—the first of its kind—hosted 120 people; this year, it was 1,200, and every single session I attended over the three-day event was packed.

An explicitly professional, Lean-In style organization for women in the weed industry is a quite specific thing, and I’d been curious about what kind of a scene I’d be walking into. The conference branding reminded me of Teach For America, the dress code prescribed was business casual, and there were rooms designated for investor meetings; the welcome email encouraged us to bring extra moisturizer for Denver’s dry climate and to “find your tribe, find your vibe, and thrive.” The whole thing was an especially warm harbinger of the swift, medical-leaning corporatization of the marijuana industry, a movement that runs at odds with the drug’s longtime stereotype as a dirty recreational substance, and may eventually counter it wholesale. Once I got to Denver, I took a shuttle ride to a female-owned dispensary and purchased a fetching little red Women Grow vape, already pre-loaded and charged up for use.

Women Grow was founded in August of 2014 by Jazmin Hupp and Jane West: two ebullient women in their mid-thirties, Hupp formerly a director for Women 2.0 (a tech-centered analogue to Women Grow) and West formerly an events producer who got fired from her previous job for vaping on camera and who later produced the famous “weed night” at the Colorado Symphony Orchestra. In 20 months of operation, Women Grow has developed 45 chapters across North America and has had 20,000 women attend its events; they host online seminars, have a lobbying presence, and maintain an extensive business directory, listing women-owned operations that deal with (among other categories) marijuana compliance, genetics, distribution, insurance, point-of-sale systems, tech, testing and HR.

Women Grow is for-profit, which is important to Hupp. “Fundraising sucks!” she yelled plainly, taking the stage after Glaser. “It’s time for us to take control of the industry, instead of being the nonprofit angels we’ve been for so long.” (The room murmured something that sounded like “Amen.”) Later, Hupp talked to me about how she and West intend to run Women Grow almost as a photonegative of the tech world, with their site citing this explicitly:

This cannabis industry is creating businesses that serve people of all genders, colors, and ages, and the best way to do that is to invite all those people into the industry. Unlike tech, where we screwed up targeting technology education to primarily young men, there was nothing about this new regulated industry that was gender specific. We saw the opportunity to create a new industry in America that [could] be fair from the very start.

Women Grow currently makes money from ticket sales to local, regional and national events, as well as online education programs (you can purchase the extremely servicey conference on video as a package for a reasonable $95) and individual or corporate memberships into their business directory. It’ll evolve as the industry does. “I want this organization to grow into whatever it needs to be to put women at the forefront of the cannabis space,” Hupp told me. “This industry is the next thing. Women are the next thing.”

I agree with the idea that women are the next thing, but after a life spent in gendered enterprises that are externally cheerful and internally something else—ballet, gymnastics, cheerleading, sorority, women’s media, you name it—I feel immune to group empowerment, and suspicious of it besides. I was surprised, as I listened to Hupp speak at the conference, to feel a lump in my throat.

This was related partly to the emotional urgency with which I had conducted that morning’s journalistic investigation of the official conference vape; it was also related to the fact that the newness of the legal weed field right now makes it a legitimate and almost singular ground for hope. There was a sincerity and wholeness to everyone’s optimism that I found affecting—they hadn’t been burned by this industry, because this industry didn’t exist 10 years ago—and a structural pragmatism, too. “Who had to arrange childcare to get away for this weekend?” Hupp asked on stage, and nearly everyone in the room raised their hands.

Hupp exhorted us to remember and “hold space” for all the women who couldn’t afford to take time off work, who couldn’t pay for childcare. She reiterated why we were all here: to make a new kind of industry, an inclusive one, one controlled by benevolent matriarchs who take care of their own, by people who’ve spent all their lives in a discriminatory, male-dominated economy and wanted to build an alternative. As Hupp talked, a woman next to me breastfed her baby in the open. Later, she got up when the baby started fussing, and the women behind her urged her to stay.

The driving idea behind Women Grow—that women are underrepresented and underserved in business—is burgeoning in many industries right now, accompanied by the perhaps more important idea that, when women are in control, they actively improve work for everyone. In other words, women aren’t just there for quotas; they are good for increasing profit, and tend to create more equitable and sustainable conditions under which to pass the day.

Women aren’t actually in charge of much, though, because of little lasting legacies like not getting the vote till this past century or the right to have their own lines of credit till 1974. The effects of systemic sexism, severe and routine diminishment of women, have recently been a major topic of conversation in Hollywood, in academia, in the music industry, in tech, in media: industries like most industries, where male domination has been standard since the start. In these conversations, we’re still mostly at the “look how bad this is” stage rather than “what’s anyone in power actually going to do about it” stage, and to me things don’t look so auspicious as much as they do entrenched.

Weed is different, because there’s no one quite so firmly in power yet. Of course huge capital investment is hovering, and will pounce as soon as there’s federal legality, and the industry isn’t exactly a blank slate: it’s expensive to get into on a large scale, which skews the population trying to enter the market, and laws barring the previously convicted further ensure that the world of legal “potrepreneurs” is extremely—like 99 percent—white. (Discrimination always finds a way in: how inspiring!) But nonetheless, the whole idea here is that rules can be rewritten. And let’s say we’d rather have this industry controlled by white women than white men—I would. Then we can acknowledge that the weed market is about to explode, that it’s about to be a Scrooge McDuck type of situation; and these women who are trying to get into that whole gold coin thing have an extremely important industry growth period on their hands.

To wit, weed is the fastest-growing industry in America: 24 states have already legalized medical marijuana, 20 states have weed initiatives on the ballot this fall, and four states (Alaska, Colorado, Washington and Oregon) sell it retail, as easy to purchase as cigarettes or alcohol. The legal weed business has an astonishing growth rate; it brought in $1.5 billion in 2013, $2.6 billion in 2014, and $5.4 billion in 2015, and sales are projected to reach anywhere from $11 billion to $35 billion by the end of the decade.

There’s a huge and obvious barrier to the aboveboard growth of the industry—the matter of weed being a Schedule 1 federally controlled substance that every year lands hundreds of thousands of (disproportionately black) people in jail. But criminal justice reform concerning marijuana arrests and sentencing may come quickest through legalization: the best argument you could make against a disabled septuagenarian veteran getting a life sentence for growing weed at his house is not that it’s inhumane, which it is, certainly, but that it’s judicially improper in a country where weed is becoming legal left and right.

So, for now, weed remains in an uncomfortable, uneven, in-between area; even when California goes recreational, as it’s expected to do in November, the billion-dollar legal industry will still be shut out of the banking system, and huge quantities of legal weed will make their way to the illegal market. The market for weed in general is large and continually expanding: there will presumably be a saturation point in the future, but marijuana supply has never caught up to marijuana demand. As of now, 41 percent of Americans have tried the drug, and roughly 6 percent self-identify as regular users. But “consumer education,” let’s say, creates a certain percentage of customers for life.

In other words, weed people don’t have to be born by way of unsociable and funky temperament; they can be made, particularly through the medical point of view. The Women Grow conference was full of women who had come to the drug through personal health issues, or who had explored marijuana as palliative treatment for sick family members and then discovered its benefits for themselves.

At a welcome dinner, I met a perky Army veteran named Mandy who had gotten into a near-fatal car accident and developed migraines so paralyzing she didn’t get a full night’s sleep for two years. Then she tried weed. “I’m a better mother now,” she told me, putting a couple of gyros in her purse for her two kids.

On a trip to the dispensary dispensary, I talked to Gaynell Rogers, formerly the head of publicity for Pixar, now the head of a PR firm that’s coordinating marijuana brands for the Doobie Brothers and Jefferson Airplane. “I thought I was going to move to Tahoe and write cookbooks. And then I got cancer. Twice,” she told me. Finding treatment hammered it home to her that “weed is a social justice issue.”

(This, about the social justice issue, was a refrain I’d hear over and over, sincerely but slightly impotently: it is impossible to feel as if your life has been salvaged by a substance without understanding how unfair it is that that substance keeps millions of people in jail. But whether leveraging your privilege to make the drug respectable will help those people or just heighten the contrast between your lives and theirs, nobody really seemed to know.)

Even outside the conference, because this was Denver, I kept meeting people with similar stories. One night, my cab driver was a white woman in her early seventies whose friendliness filled the minivan like smoke. She got visibly excited when I said why I was in town. “Oh!” she said. “Let me tell you my story about marijuana! I have a real bad shoulder—my three dogs just pull the heck out of it—and a few weeks ago, my massage therapist said, you know what you should try?”

“A topical?” I said. “I just tried my first one today. Did it work?”

“YES,” she said. “At first I was like, are you kidding me? I told my therapist, I’m not smoking anything. I tried marijuana when I was younger, and I just stared at the wallpaper! I didn’t like it at all! But I walked into the dispensary and they fine-tuned the dose for exactly what I needed, and I swear, it’s a miracle.”

She had two blue heelers and a pit bull, she told me; she’d formerly run a rescue group. “But no one tells you how much you need your shoulders until after your dogs mess them up! I couldn’t even dress myself! Until I found a solution!”

“And a fun one,” I said, and this nice woman and I laughed merrily about our shared love of a federally illegal substance that we have both been able to use freely, which has not put us in the criminal justice system, which will not ruin either of our lives.

Throughout the conference, I got regularly flattened by the mental vertigo induced by trying to simultaneously think about weed’s two legal statuses—these two parallel Americas, in which the state alternately serves or dismantles your interests. It would be impossible, for one, to imagine a version of this conference that drew 1,200 young black men in mutual celebration of their place in the legal marijuana industry instead.

Everyone does drugs; white people do slightly more of them. But what you look like in this country tends to determine how illegal certain activities will be for you, and weed brings this fact out on a depressingly large scale. There were 8.2 million marijuana arrests in the United States from 2001 to 2010; an insane 88 percent of these were for possession, and black people were 3.73 times more likely than white people to be arrested for the crime. In 2011, there were more arrests for weed than for all violent crimes combined, and there are still over 600,000 possession arrests every year.

And here I was at a business-casual women’s conference in Denver, about as safe a zone to vape your heart out as you could get. The acknowledgment of this fact was constant but minimal: there was lots of talk of weed and criminal justice—I also don’t mean to downplay the real danger the women there faced against CPS and police themselves—but there was no time wasted loudly calling out the white privilege enjoyed by most people in the room. (I do mean “wasted” there; I can imagine nothing worse than a room full of white women saying how lucky they are to be white.) There was a diversity session, and a queer-tinged frankness about everything—anecdotally, Women Grow estimates its LGBTQ population at double the national average—and a sense of intentional inclusivity that I haven’t sniffed out in years.

The longstanding demonization of marijuana in America makes it easy to forget that things weren’t always like this—that a relatively neutral substance wasn’t always the playing field on which wild games of social division were quietly, constantly fought. Even hemp, a non-intoxicating, industrial, fraternal twin to marijuana, has been outlawed since 1970: it only became re-legalized to grow even for research purposes in 2014.

As any college stoner might tell you: centuries ago, we weren’t so deep in all this bullshit. King James ordered colonists in Virginia to grow 100 hemp plants each; Louisa May Alcott once ended a short story with the line “Heaven bless hashish, if its dreams end like this.” You could be jailed in Virginia in the mid-18th century for not growing hemp in your fields during times of crop shortage, and weed was used medicinally as early as colonial times and recreationally from the mid-19th century on.

Then, in 1906, Congress started passing laws to regulate the market for unlabeled and untested substances; state by state, cannabis was added to lists of habit-forming drugs, and then, to lists of poisons. Anti-immigrant sentiment, exacerbated by the Great Depression, created an intense public distaste for farmworkers who used marijuana, and states began to outlaw the substance completely.

In 1930, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was established, with a director named Harry Anslinger who made the racist undertones of weed laws clear, writing:

There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz, and swing, result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and any others.

And there, with our extremely lit inaugural drug czar, we were well on our way to the current situation in America, in which weed is a Schedule 1 substance, along with cocaine, MDMA, acid, heroin, and meth.

The Schedule 1 category denotes a high potential for abuse as well as a lack of known medical benefits. Weed’s abuse potential is debatable, but in the relative scheme of things, it’s moot: the New York Times wrote in 2014, in a strongly worded recommendation for federal weed legalization, “We believe that the evidence is overwhelming that addiction and dependence are relatively minor problems, especially compared with alcohol and tobacco.”

But the argument that weed has no medical benefits is plainly wrong. Though there are other things on the Schedule 1 list that can be used therapeutically—MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder, psilocybin for cluster headaches, LSD for depression—weed is mild and palliative; it could feasibly be used primarily in a medical sense. I’m a recreational smoker, but it’s become obvious to me, in an adult life full of dumb behavior but also taxes and dog-walking and cleaning the house on Sunday and settling down at the computer at 10 p.m. on weekdays to go through thousands of words of a draft, that I use weed therapeutically, if not necessarily medicinally. I use it to calm down, to work better, to access some productive emotional vulnerability, to keep my sense of anxiety skewing positive, to feel interested in mundane and necessary tasks.

If I think too much about this, it feels slightly depressing: look, see, here’s how well weed helps me optimize while overextended even in a party sense and/or produce signs of worth within an exhausted, broken culture! But then again, I could say that about anything else I like. And anyway, there is no other Schedule 1 drug you could use on a near-daily basis for a decade and function much better than you would have otherwise, a statement which isn’t true for all weed smokers but certainly is for me. I can forgo pot much easier than I can abstain from coffee, but I have done enough intensive personal research to know that weed improves me; others at the conference, people who’d had cancer or who suffered from epilepsy or arthritis or lupus or MS, were speaking more seriously. Weed, they said, had saved their life.

“Cannabis is the female plant,” intoned Melissa Etheridge, who took the stage in a leather jacket and aviators. “It’s the female spirit demanding attention. It’s bringing back the pagan knowledge we have about wellness that we were burned at the stake for. It’s the feminine energy missing from the female plane.”

Long a marriage equality activist as well as a musician, Etheridge, after surviving breast cancer, is now an advocate for legal weed (and, of course, a weed businesswoman who sells things like “weed-infused wine tinctures”). During her speech, she made a joke about drug use among Americans being “don’t ask, don’t tell,” then compared coming out as a stoner to coming out full stop. “You have to be confident about who you are, to your friends and family and the people in your neighborhood. You have to deal with the stereotypes and break them.”

Etheridge said she’d never been much of a drug user through decades in the music industry (“What was around was the really awful stuff, like cocaine”) but then, in 2004, she got her diagnosis. “I was starting chemotherapy, and David Crosby, you know him? He came up to me, and said, Melissa, you simply must try cannabis.”

She was lucky, she said, to be in a place in her career where she could afford to take a couple of years off work altogether. “And so, when I went through chemo, they took me as close to death as they could get. I was smoking weed to be able to talk to my children, to function. I smoked constantly, then I couldn’t smoke anymore and I vaped, and then eventually I had to eat it. Butter on potatoes: that’s the only thing that got me through treatment. I didn’t take steroids or pain medicine. I came out of it thinking—there’s something deeply wrong with the world if this is illegal.”

Then Etheridge picked her gender proclamations back up and reversed them. “Money was the system. It was them,” she said, meaning men. “It wasn’t us. We did the free services. We helped out. But the way we need to balance the masculine and feminine energies in the world, we need to balance those energies in ourselves. We need to make the money. We, as women, will create corporations that we won’t have to fight against. We can show them how to do it. Cannabis will change the entire conversation around health.”

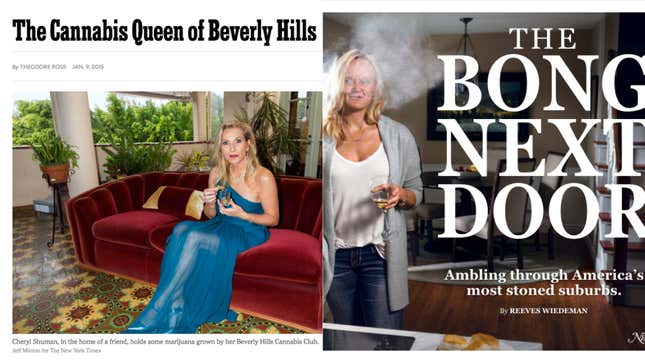

Before cannabis changes the conversation around health, it’ll be up to women to change the conversation about cannabis. Women control around three-quarters of consumer spending and make 80 percent of family health care decisions, and it’s the “safest” of these women, i.e. white middle-class mothers (and the children and elderly parents whose healthcare they provide) that’ll be the magic bullet in this conversation.

When white moms use weed, People writes about them: “Utah Mom Chooses to Illegally Treat 3-Year-Old Daughter With Cannabis Oil,” for one. New York covered religious suburban moms and their Stoner Jesus Bible Studies last year, too. White women who are invested in the weed industry—think Broad City’s Ilana Glazer telling the New Yorker she smokes every day—almost always provoke some combination of amusement, bemusement, and respect.

But there is a reason why the demographic that would be most immediately useful to the marijuana movement is the one that probably least understands it, or openly acknowledges it, as a whole. Weed’s reputation is unsavory primarily because of its illegality: the population of open users has been necessarily composed of people who are comfortable with unlawful activity, and the criminal population slants poor, black and brown. Weed’s effects also slant towards things that a certain type of rich, white, conservative woman avoids for social reasons—like eating, or arousal, or vulnerability, or embarrassment, etc. And so weed’s association with “sketchiness” has endured.

Nevertheless—to return to the presupposition that many of the habits of our time are indicative of acceleration, badly won comfort, and general anxiety and duress—let me suggest that this segment of the population, i.e. women in general and/or white women specifically, needs weed more than anyone else. Decades of weed being positioned as a gateway substance have papered over the fact that weed can also be a plug for a hole that’s currently being filled quite dangerously. Women are binge-drinking 36 percent more now than 10 years ago; almost 200,000 women visit the emergency room every year because of painkiller intake; around 6,600 die of pill overdoses annually. And so on.

And here’s where the line between recreation and medication gets blurry: if we’re talking about substances here, you can choose your statement of purpose, but either way you’re alleviating pressure, you’re filling a need. Pharmaceuticals alleviate pressures, and pressures fall more heavily on women—social expectations, the obligation to do unpaid work caring for others—and so women, as a result, are more dependent on prescription painkillers than men; they are more likely to be prescribed them, and they are more likely to become addicted. The effects of these medicines can in many cases be simulated or at least approximated by a much less addictive substance: weed.

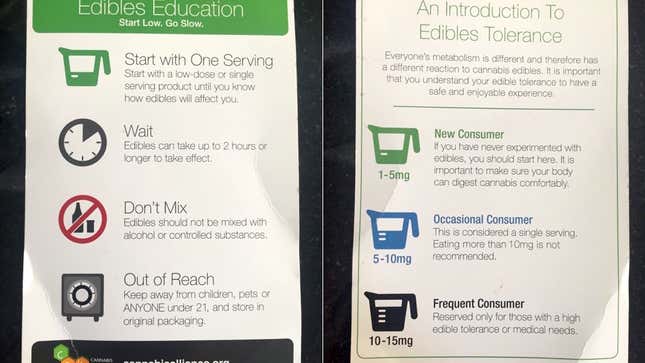

And of course weed doesn’t suit everyone—coffee doesn’t, and neither does wine. Neither do pills. But the world of legal weed allows for an experience with the substance that is controlled, tailored, and otherwise unrecognizable from that one time someone gave you something in high school and you suddenly felt like the air was burying you alive.

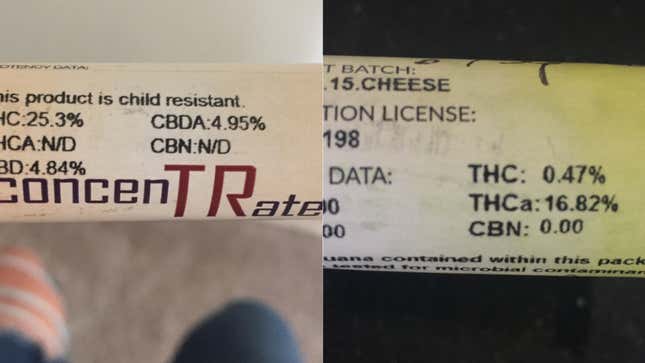

In these new markets, weed is now tracked “seed to sale.” It’s tested batch by batch. It’s calibrated to two percentage points for the active substances CBD and THC, which are usually present to various degrees in bud marijuana and have dramatically different effects. Specifically, THC is psychoactive; CBD is not. THC causes excitement, which can turn into anxiety or paranoia, as well as sleepiness; CBD decreases anxiety, keeps you awake, may have anti-psychotic properties, and counteracts the trippier effects of THC.

Before the recent advances in weed technology, the difference between THC and CBD for users mostly came up when choosing between indica and sativa, the two types of weed strains. Sativa, a skinnier-looking plant, is heavier on the CBD; it’s “day weed,” a head high, cerebral and amusing, and the kind I smoke when I need to work. Indica, a shorter and fatter plant, is heavier on THC; it’s “night weed,” a body high, the kind that locks you to your couch and makes you want to take a bath or go to sleep or have sex, or all three in a different order. And there are lots and lots of indica/sativa hybrids too: one of my favorites is called Larry OG and makes my body and mind both feel extremely interested, and Blue Dream, one of the most nationally popular strains, is a hybrid that relaxes you physically while perking you up.

Now, as was on dizzying display in the Denver dispensaries, you can not only calibrate the substance you’re taking with unheard-of precision, you can change the mode of intake to suit your exact needs. If you want pain relief or mild relaxation and nothing else, you can rub a weed salve on your neck and shoulders; you can take a bath with weed salts; you can put a CBD-only patch on your skin. If you want to get a little stoned for whatever reason—for fun, or for anxiety relief, or to sleep, or for creativity, or to replace a drink or two while you’re out—you can get pre-rolled joints of any strain you want, or a pre-loaded vape, or vape cartridges that tell you exactly what you’re getting on their container. For people trying to get aggressively and recreationally high, there’s dabbing, lighting up a chunk of wax with a blowtorch, and there are formulations-behind the medical counters, always separate from the recreational counters—tailored for every specific medical purpose imaginable, including medical use for children and the elderly and pets.

Of course, the prospect of weed that’s cultivated for unprecedented potency and tailored with pharmaceutical precision is mildly alarming in its own right; it sounds like quick-fix magic, like soma with less of the dystopia part, like something that might smooth down everything prickly about you without you having to de-prickle on your own. Then again, not to repeat myself, a lot of things in contemporary society are like this. And while the possibility of pharmaceutically designed, scaled and distributed marijuana ensures that big conglomerates will be in this space as soon as is legally possible, bringing decidedly non-cooperative incentives to bear (and shutting out a good amount of these new-structures ambitions), weed also persists in 2016 through a unique lineage of counterculture. A strong degree of resistance—a type that’s crucial to Women Grow’s project—remains. For the precious few years in front of us, the rules haven’t yet fully been written; it’s still, for the most part, anyone’s game.

Anyway, I spent a lot of time in Denver test-driving what was around me—sativas mostly, in the interest of being able to report from the conference and simultaneously work most of the days remote—and frankly, this weed ruled. I tried different kinds of weed oil in a vape, all various levels of mellow and suffusive and stimulating, with the quality control really making a difference; all the bottom notes of paranoia or dizziness or fuzziness are gone. I bought a couple of joints there, too, and normally I couldn’t smoke a whole joint the size of these fat little creatures by myself without feeling like I needed to get in a pool immediately and not speak to anyone, but this weed was beautiful: clean and plumey and strengthening and light. I kept trying to blow the selfie camera opaque with smoke; I felt pretty and inconsequential, like my sense of self and my actual self had lined up with each other, and that both were the right size.

But the real difference is the recreational dispensary. I’ve been accustomed to dispensary life since I went to graduate school in Michigan, which has a medical weed program (which I snuck into thanks to a case of active tuberculosis I contracted while in the Peace Corps; thanks, TB!) and it’s so much better, so uncool and silly and bland and above-board. The recreational dispensary took this a step further, into full nerd territory, which is perfect. Weed is not interesting enough to be associated with the forbidden. Legalize it, and young black dudes can walk around with a joint without getting rolled up for Class B misdemeanors; college girls can get an eighth to smoke with their roommates without having to track down a drug dealer who’ll lock the car doors and chop out a line of coke; moms can fall asleep without taking 20 mg of nightly Ambien, or treat their severely epileptic children with a drop of CBD tincture under the tongue without being afraid to tell their doctor what’s suddenly working so well; grandmothers can try some weed to invigorate their gardening practice without having to ask their shitty nephew to ask their skulking friend who knows a terrible guy who’s never taken off his beanie. All of these people, they could just walk right in.

Leaving the Women Grow conference, I made a last stop on the way to the airport: Medicine Man, the largest single dispensary in Denver, founded by brothers named Pete and Andy Williams. It was a reality check, after being in the company of so many women; Medicine Man was insanely efficient, intimidatingly regulated, and staffed, at least that day, mostly by men.

Because weed businesses are cash-only and move a lot of profit—Medicine Man was bringing in $50,000 per day at the end of December 2014—they are uncomfortably and forcibly secured. I got there early for the tour (which Women Grow had organized in the middle of Medicine Man’s all-day, technical and extremely granular seminar about industry best practices) and a male security guard with a gun in his holster stopped me to take down my ID and information; the guy behind the counter, who sold me some excellent oil cartridges, leered.

The women from the tour, polite and taking furious notes and photos, showed up. We were led inside the Medicine Man facility, which is enormous: 40,000 square feet. Inside, it was clean white, Willy Wonka futuristic, big hallways leading to mostly closed-off rooms holding thousands of marijuana plants, all monitored by machines that were originally built for Apple and Google’s server room; here, they checked levels on temperature, humidity, C02. Unassuming twentysomething men walked around in navy scrubs, wearing headphones; they were in charge of watering, scrubbing, checking, noting.

The room in front of us was called The Green Mile, holding plants as far as the eye could see under a bluish light that made their leaves look iridescent. The plants in this room, the guide told us, were in the initial vegetative state. In this phase, a plant hasn’t showed its gender yet, and the gender it evinces is important: only female plants grow buds.

“All the plants in the building are female,” said the tour guide. “We do everything we can not to surprise them with any change in conditions. If a plant gets stressed, it’ll try to sex itself. It’ll become a hermaphrodite plant.”

Well, I thought, I guess the weed industry is dominated by women. We walked down a long bright hallway that made me feel like I was going through the back entrance to heaven; the weed smell felt natural and permanent, like the smell of salt at the beach. Later, on the way to the airport, my cab driver would pull out a bottle of Tommy Bahama cologne and spray me because he was concerned I wouldn’t make it through security.

We peeked into another room, with shelves and shelves of flowering weed plants sitting under enormous, rectangular, sun-bright lamps. We huddled around the door, everyone’s eyes enormous. This—what Medicine Man has, a company bringing in tens of millions of dollars a year in profit, a top-to-bottom organization that’s beginning to make its shares public—was what they, these moms, these women, wanted to build.

One woman asked how many days they keep the plants in the light.

“Mothers never see a decrease in their light,” the man said, closing the door to the room where the weed plants were growing. “They think it’s perpetual spring. They grow up and up and up.”

Contact the author at [email protected].

Illustration by Jim Cooke