In 2009, Ashley Jordan went to a party at her friend Thomas Oliver’s house in Portland, Oregon. The two had met a few months earlier at a bar. They had a few friends in common; both were part of a small scene that centered around the local music community. It was towards the end of the evening and most everyone was sitting on the porch when, Jordan recalls, Oliver started being obnoxious and she began to poke fun at him. “I made a light joke at his expense and people laughed,” Jordan remembers. “Then I just saw his expression go black. I’d never experienced someone looking at me with pure violent rage like that before. It was instantly frightening.”

Jordan claims Oliver grabbed her, pushed her, and slapped her. She says he told her, “You think you’re smarter than me, don’t you? You always have. You think you’re better than me. You think I’m dumb.” The people on the porch quickly dispersed. Jordan says Oliver dragged her across the house to the bathroom and threw her into the tub, threatening to urinate on her: “I started screaming at him and the noise I was making concerned him enough that he yanked me out of the tub and told me he wouldn’t if I shut up. He used the toilet with one hand so that he could keep the other one on my arm, preventing me from escaping. My head was throbbing from where he’d hit it on hard edges multiple times and I was sweating with fear by this point.” When he finished urinating, Jordan says, Oliver let her get onto her feet to walk up the stairs to his room.

“I thought about trying to run, but he was right behind me,” Jordan recalls. “I knew if I went upstairs I was going to be in trouble, but I didn’t know how to escape.” When they got to his room, Jordan alleges that Oliver tore off her clothes despite her objections: “I was struggling to keep them on and begging him to stop. I repeated over and over that I didn’t want to do this. That I wasn’t joking around. He told me he could do whatever he wanted, because I couldn’t stop him.”

For the next several hours, Jordan alleges that Oliver punched her in the face, subdued her with strangulation, and raped her. Afterwards, she says she waited for him to fall asleep so she could escape. “I put my clothes on in the hallway and ran. When I got home I basically collapsed on my stairs and cried. Besides the physical suffering, I guess it felt like a loss of something innocent in me that maybe hadn’t quite learned how awful the world really is.”

In the months following Jordan’s alleged rape, she says she lost a quarter of her body weight, dropped out of school, and stopped going out. Despite the immense pain she was feeling, she initially chose not to report her attack—she and Oliver had slept together before, and she was drinking that night. Jordan worried that police would not look favorably upon these details. What’s more, Oliver was a well-known indie rock photographer and videographer in Portland, and Jordan worried that people would believe him, not her. “He was too popular and too important,” she told Jezebel.

Four years later, Jordan learned through friends that Oliver had been arrested for solicitation of sex workers. “I had to drop any delusions I’d had that what happened to me was an isolated incident,” she wrote to Jezebel in an email. She called Detective Nathan Sheppard at the Portland Police Bureau and filed a report. In the following year, as Detective Sheppard built his case against Oliver, the police asked her not to talk about her experience publicly.

On May 26th, 2017, Oliver was arrested and charged with 55 crimes that involved six different women, including Jordan. The alleged offenses include rape, sodomy, kidnapping, and sexual abuse, and occurred between June 2007 and March 2013. His bail was set at $5.4 million. (Oliver’s attorney declined to make Oliver available for comment on this piece. Oliver has entered a not guilty plea and his trial is set for October 31 of this year.)

The day of Oliver’s arrest, a former friend of Oliver’s from the Portland music scene posted an article on Facebook about the arrest. In the hours and days that followed, hundreds of comments flooded in beneath the original Facebook post. Many people shared their sympathy with the alleged victims, while others expressed shame and disbelief that someone within their progressive, liberal community could have been capable of such violence. Some commenters suggested that there were people in Oliver’s circle who knew about his alleged crimes, but that they chose either to distance themselves or ignore them altogether. What stood out the most to me, though, were the women who wrote on the thread to claim that Oliver sexually assaulted them, too.

“I guess I will share my experience,” wrote one commenter, whom we’ll refer to as “Rebecca,” but whose real name Jezebel is withholding at the request of the DA, since Oliver’s trial is ongoing. “I didn’t want to make this public but I think it’s important enough,” she continued in the post. “I don’t remember a lot because of alcohol and repression, but Tom did assault me and I see that now. He got me into his room to take a photo of me (I was an aspiring model who just wanted to be liked—easy prey). All I remember is finding him really gross and creepy, and him advancing on me. I remember not wanting it. I don’t remember anything else.”

Like other women who posted on the thread accusing him of assault, Rebecca says she never filed a police report, and was not part of the police investigation against Oliver. As Rebecca read through comments by other women on the thread, though, she felt compelled to share her own experience. “I read through every single comment, and so many of them were almost exactly like my story,” Rebecca said in an interview with Jezebel. “I was talking to my friend about it, and she told me about things that happened to her. We were like, ‘Do we need to say something? Eventually I was just like, fuck it, I might as well.

“It’s a lot easier to emotionally distance yourself over social media because it’s just text,” she explained. “While it’s obviously part of you, it’s easier to be like ‘I’m gonna write this out, and then I’m gonna walk away.’”

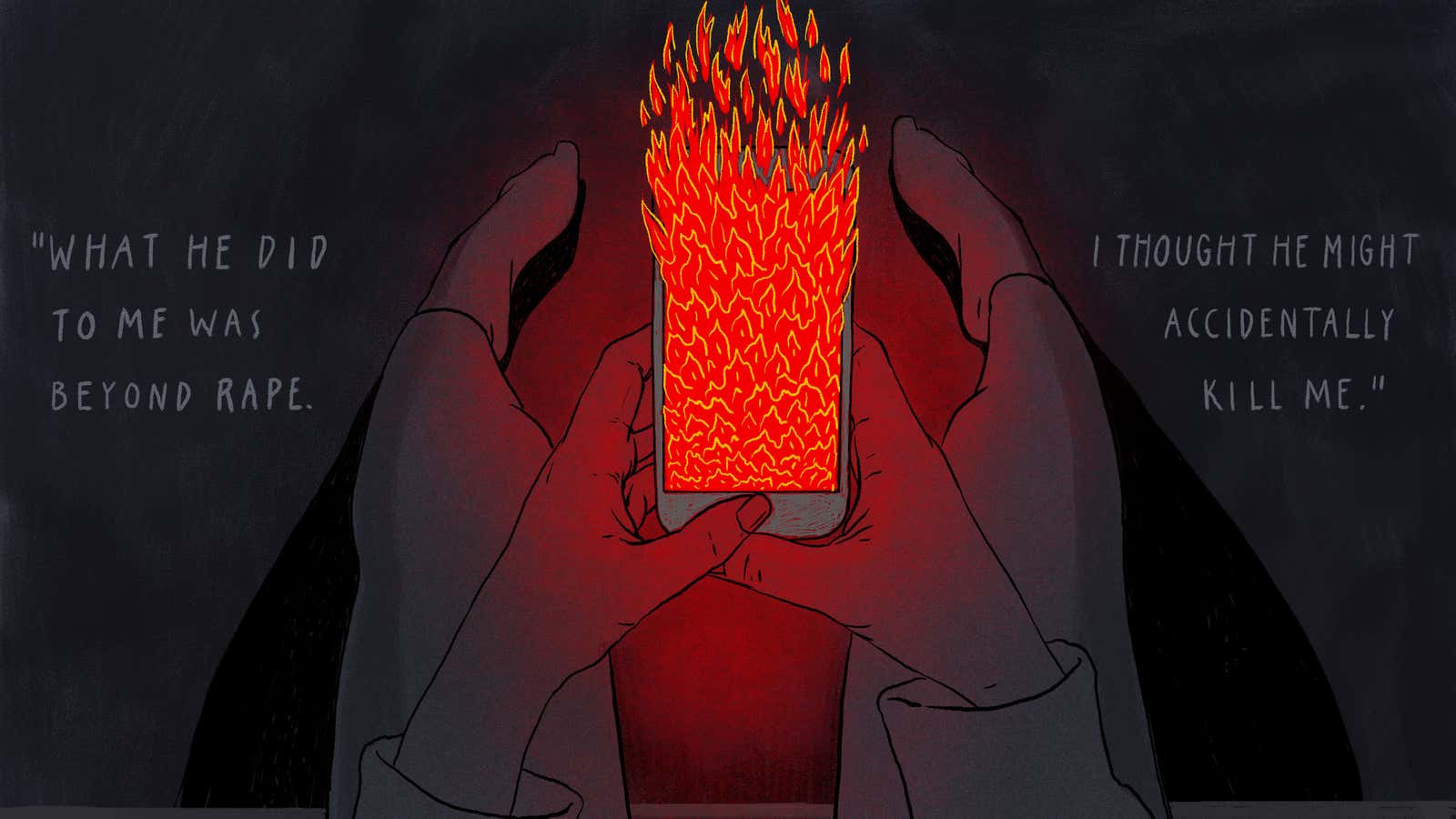

Jordan, now 33, posted to the thread several hours after Rebecca: “Fuck it. Wasn’t ready to talk publicly about this yet and I have zero trust or faith in anyone in this shit city because of my experience telling people about this, but I am one of the six women he has been arrested for... What he did to me was beyond rape. I thought he might accidentally kill me.”

When I met with Jordan at a small coffee shop in Portland in late June, she was warm and composed. From 2009-2011, I was on the periphery of a social scene that included Oliver, but Jordan and I never crossed paths. When I saw her comment on the Facebook post about Oliver, I decided to reach out to her to see if she might be willing to talk to me. Once we sat down in person, Jordan spoke about how her post allowed her to disclose pain she had been keeping from even her closest friends and family for years. “I wanted to comment to put a face and name to the word ‘victim’ in that headline,” Jordan told me. “I knew a lot of girls reading that were probably victims of Tom. I wanted to offer my support, and identify myself as one of the victims to offer a resource for women who had questions or wanted to come forward.”

Talking about one’s sexual assault on Facebook allows survivors to build a community against the backdrop of a criminal justice system that often leaves them feeling isolated and alone. Whether it’s a result of the increased media coverage of rape on college campuses, celebrity cases, or the President’s repeated sexual transgressions, there has been a noticeable shift in the public discourse surrounding rape and sexual assault—many women are openly and publicly talking about their experience in a way that we haven’t really seen before. And there are a lot of survivors; according to RAINN approximately one out of every six women has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape.

On Twitter, hashtags have created a space for survivors to vent, connect, and share their stories. In a March 2016 essay titled “What I Know,” writer Jessica Knoll claimed that the rape scene in her novel Luckiest Girl Alive was based on events in her own life. Knoll tweeted, “For 17 years I was too ashamed to share this. Today I am not ashamed. Proud to tell #WhatIKnow.” Women on Twitter swiftly responded to thank Knoll and express their support using the same hashtag.

In the aftermath of President’s Trump’s leaked conversation with Billy Bush on Access Hollywood, writer Kelly Oxford tweeted, “Women: tweet me your first assaults. they aren’t just stats. I’ll go first: Old man on city bus grabs my ‘pussy’ and smiles at me, I’m 12.” Within minutes, survivors began responding with their own stories—assaults ranged from being groped on the subway to being molested by a family member. Oxford later followed up, “women have tweeted me sexual assault stories for 14 hours straight. minimum 50 per minute. harrowing. do not ignore. #notokay.”

According to a study done by Bar Ilan University professors Dr. Hadar Dancig-Rosenberg and Dr. Anat Peleg, victims’ motivations for posting on social media vary: They can break a code of silence, relieve loneliness, and seek justice and accountability. Talking about the incident is a way to tell the story on a survivors’ own terms—no one can speculate that perhaps they were assaulted because they were wearing a short skirt, had too much to drink, or went home with a guy on a first date, when the survivor is the one doing the talking. Writing about one’s assault publicly helps to debunk the notion that a woman could have possibly played a role in her own assault.

And when taking a closer look at our legal system, it quickly becomes clear why survivors are turning to social media. When investigating a report, detectives are obligated to ask victims to describe their rape in painful detail, as was the case with Jordan. Sometimes these interviews even take place in police interrogation rooms. If a case goes to trial, it’s standard for defense attorneys to ask deeply personal questions in a public setting, that can feel irrelevant to survivors. Emily Doe, in her now famous letter to assailant Brock Turner, recalled some of the questions she was asked by his attorney: “What were you wearing? Why were you going to this party? When did you urinate? Where did you urinate? Are you serious with your boyfriend? Do you have a history of cheating?” With these kinds of practices in our criminal justice system, it’s unsurprising that survivors are often left feeling alienated and shamed. “Whisper networks” that operate outside of the justice system of women warning each other about dangerous men have existed from time immemorial, so a move to social media is, well, natural; discussing one’s experience on social media, either about the assault itself, or what they felt was an unfair trial, allows women to seek the comfort and support they may have felt they weren’t given when they reported their rape in the first place.

There is a difference, however, between disclosure or sharing, and accusations. Communities no doubt have been formed by survivors who disclose their rape without actually naming their rapist. In the case of the Facebook post about Oliver and the comments below it, though, women came forward to accuse Oliver of assault by name. In the days after the initial post, and the subsequent accusations against Oliver that resulted, some commenters suggested that the women who were speaking up needed to be aware that what they were writing could be seen and used against them by a defense attorney. To receive some clarification on the subject, Jordan spoke with Detective Sheppard, and shared a message from him on the thread about Oliver, the same one in which women shared their stories:

Greetings, this is Detective Sheppard with the Portland Police Bureau. I applaud all who have come forward thus far, and hope those who have not are able to find that extra bit of strength to do so. That being said, I wanted to remind everyone posting here that this forum is public record. I in no way wish to muffle public discourse, but please know if you posted here it’s highly likely a defense attorney or defense investigator will try to contact you. You have no obligation to speak to them. It’s also important to understand that deleting a post does not really mean it can’t be retrieved from Facebook through a subpoena.

After that, the thread died out completely.

Whatever a survivor’s reason for sharing their story—to get something off their chest, to connect with other survivors, or to call out people in the community who aren’t doing enough to lend their support—social media provides an audience, and forces that audience to confront the issue. This is not, however, any guarantee that the ensuing confrontation won’t be messy. “The highest and noblest purpose of social media is revolution and social change,” Jordan says. “I don’t think any other avenue would allow things like this to happen or to be so effective—it’s having the accountability of something being recorded, and it’s bringing people together that are not normally together.” But to turn one’s story over to the jury in the comments section is not necessarily a guarantee of nobility or justice.

Facebook and Twitter’s responsibility, as platforms, regarding posts that deal with disclosure and accusations of sexual assault is unclear—neither company has provided resources or policies regarding the use of their platforms in this way. Earlier this year, Facebook announced that they would begin using a new algorithm to comb through posts and look for potentially suicidal content, but as to whether or not they employ the same type of technology for posts related to sexual assault, Global Head of Safety Antigone Davis offered only this:

Facebook stands with victims of sexual assault. We are always pleased to see people come to Facebook to share experiences and build community, particularly around something as serious as this issue. We have long standing partnerships with organizations like the National Network to End Domestic Violence who provide regular feedback about our products and services, including in the design process. We’ve built tools – like blocking and our extensive privacy settings – to give people more control over their experience on Facebook. Our team also works in the community to help educate people – among them, survivors of domestic violence – on how to stay safe online.

The criminal justice system does not generally favor those who choose to speak about their sexual assaults on social media. If a victim files a police report, then later chooses to share the details of his/her assault on Facebook, a tactic for defense lawyers is often to find inconsistencies in their retelling to use against them. “Defense lawyers love social media—something as simple as the rape happened at 2 am on July 11th, but the victim writes on Facebook that it happened the night of July 10th. The defense lawyer can say, ‘Well this person doesn’t even know the date she was raped.’ That’s all it takes,” explains Colby Bruno, Senior Legal Counsel from the Victim Rights Law Center. While defense lawyers mine social media for inconsistencies in a victim’s story, prosecutors and those representing rape victims generally urge their clients to stay off the internet during their trial. “The bottom line is: where do your priorities lie?” Bruno says. “Is your priority in getting the person convicted? If it is, you have to turn off social media. Is your priority gathering a community of people? Telling your story? Creating that solidarity? Then go for it.”

It seems counter-intuitive that the desire for justice and the desire to tell one’s story publicly are at such odds with one another when it comes to sexual assault cases. In my interview with Jordan, she repeatedly emphasized the isolation that she felt in the time between reporting her assault and Oliver’s eventual arrest. It was only when she shared her story on Facebook that she began to feel a bit less alone. “I think feeling useful is positive,” Jordan says. “For the first time, there was a certain sense of strength because women were able to stand together instead of being isolated—so many of us were rejected when we tried to talk about this in the past.”

One might assume that if more survivors came forward on Facebook or Twitter, a prosecutor may be able to use that information in court to build a stronger case against the perpetrator. But, according to Bruno, that hardly ever happens. “Unless there is a very specific pattern to the assaults, then that’s the kind of evidence that isn’t really admissible,” she says. “The bias outweighs the benefit.” A prosecutor is rarely able to pile one assault on top of another unless there is a very particularized pattern to the way the perpetrator went about the rapes (this was, for example, one of the tactics used in the Bill Cosby case), and if it is within the statute of limitations.

Given these obstacles, the statistics on sexual assault and the legal system may seem less and less shocking: According to RAINN, out of every 1,000 rapes, only six rapists are incarcerated. While Bruno and her colleagues at the VRLC provide legal counsel for rape victims, they also recognize the massive systemic issues in our courts. “We don’t even think about the criminal justice system anymore as a viable option,” she says. “It will never reform so substantially that victims will feel like they have been heard.”

When a survivor speaks publicly about his or her sexual assault, it hinders the odds of winning a case, but, as Bruno points out, those odds are stacked against them to begin with: “Most victims know that their criminal case won’t go anywhere, so they don’t feel like they’re sacrificing anything if they go on social media.”

What’s more, a perpetrator’s arrest doesn’t always feel like such a great victory for survivors, especially after enduring months (perhaps years) of court proceedings. For Jordan, Oliver’s arrest did not provide her with the relief she was hoping she might feel. “It’s a really joyless victory to have. People say ‘congratulations,’ and I know what they mean, but it just feels joyless.”

Perhaps the other women who posted on the Facebook thread felt similarly about Oliver’s arrest—it’s devastating that his alleged behavior went unchecked for so many years. Who is responsible for that? The police? The local community that repeatedly lauded his artistic accomplishments in spite of his reputation? The friends that stood by him after multiple alleged transgressions? For Jordan, a public dialogue surrounding all of this is just as important as Oliver’s arrest. “People want to blame this kind of behavior on mental illness or something deviating from the norm, when this is the norm. When you acknowledge that, you are also acknowledging that it’s a social issue. And when it’s a social issue, it’s everyone’s problem.”

And when posts like Jordan’s receive enough attention, alleged perpetrators can be held responsible—even if it happens outside of the legal system. For example, in January 2016, musician Amber Coffman accused former publicist Heathcliff Berru of sexual assault on Twitter. Other women in the industry then came forward to share similar stories, and the news quickly reached major media outlets. Artists and labels that had previously worked with Berru promptly severed ties, and eventually, his firm, Life or Death PR, dissolved altogether. Berru issued a statement in L.A. Weekly in which he apologized for his “alleged inappropriate behavior,” and announced that he was checking himself into a rehab facility.

Several days after our interview, Jordan emailed me with some additional thoughts she had since we met. She wrote:

“I was also thinking about your question of why I chose to talk about it and what I got out of sharing on social media and I think it was maybe more introspection than I was capable of right on the spot.:) I was thinking about it after meeting with you and I think a lot of it was defiance. With an arrest looming and the psychological toll it was taking on me becoming more and more obvious, I felt like I was going to have to start telling people one way or another. I really, really dreaded those initial confession conversations and how people would respond, so posting something to Facebook felt like ripping the bandaid off and saying, “There, now you all know. Do what you want with it.” It was a relief. As I told you, plenty of friends disappeared after that, but most of the support I received surprisingly came from strangers and acquaintances. I think a positive part about coming forward with these experiences is that it allows you to find better support systems.”

One of the most tangible outcomes of the Facebook post about Oliver was that it allowed Jordan to connect with another person who was involved in the case. During the investigation, the six alleged victims were not allowed to speak to one another—in fact, they did not even know each other’s names (alleged victims are often sequestered in sexual assault cases so that it doesn’t appear that they colluded with one another). While reading through the comments on the thread, Jordan saw a post by another woman who had identified herself as one of the other five involved in the case. “After so much anticipation it was very emotional to see her face and her name and be able to introduce myself and say, ‘Me too.’” Jordan says. “You’re so alone in this for years. Meeting a woman who I’d always seen, even when she was just a number, as a comrade in my struggle for justice, is one of the very few happy moments situations like this can offer. I instantly felt that weight of isolation lift a bit.”

I found Jordan’s story both heartening and tragic. It’s a comfort that two women were able to build strength from one another in the face of something so terrible. But it’s tragic that this couldn’t have happened years earlier. What if Jordan had been able to know who the other victims were right off the bat? Could that have lessened some of the loneliness she felt during the investigation?

Jordan recalls that after her Facebook post, many women reached out to her with similar stories, “I have an entire message folder full of women who messaged me ‘this happened to me.’ Not necessarily by Tom. It’s not something they can talk about. When you open that door for them, you find out how many people are out there keeping this a secret.”

Anna Oseran is a writer based in New York.