Zebedee spends her days largely alone, nervously swimming in a clear aquarium, there for the entertainment of tourists dining at Abu Dubai's Burj Al Arab hotel. Surrounded by only a few fish, with nary a male shark in sight, Zebedee has defied biology. For the last four years, the tiger shark has experienced so-called "virgin births." Zebedee, it seems, is a misandrist's dream; she reproduces parthenogenetically, meaning that her embryos are developed from eggs unfertilized by male sperm. Her offspring are nearly identical to her, and their unique DNA structure is the result of her own DNA recoded and recombined during reproduction; they are so genetically close to their mother that they are nearly clones.

While Zebedee's large number of virgin births is a rarity, the process itself is not quite as unusual. Parthenogenesis has been observed in honey bees, crayfish, birds, another shark in Detroit. Flora, a Komodo dragon in Chester, England, hatched her own tiny miracles in time for Christmas. There is almost an entire animal kingdom born of virgins.

The biological reasons for parthenogenesis are not widely understood. Some scientist have suggested that the reproductive process might be an evolutionary adaptation—a method by which the female of a species can re-populate and maintain their entire species without their male counterparts. Perhaps it's biology's poetry; a colony of women reproducing an entire species sounds almost like the plot of a Doris Lessing novel.

Parthenogenesis—from Greek, literally meaning "virgin birth"—is compelling because it disturbs, it inverts so much of what we understand to be natural reproduction. It's also deeply imbued with a kind of mysticism tied, as the virgin birth is, to origin stories of gods.

But Zebedee's children are not gods. They are fragile and their survival is threatened by the very process that made them. But yet they fascinate; their very presence speaks to the possibility of earthly divinity. And the body of their mother—of the female who reproduces parthenogenetically—represents something even more coveted: the miraculous interweaving of sexual purity with reproduction.

Unlike virgin births in humans, Zebedee's births are not miraculous; they have been quantified and observed, there are rational hypotheses. There is no debate about the reality of parthenogenesis. No one argues over whether or not the process is real, a myth or a metaphor.

There is no evidence that a mammal have ever reproduced by this method; as far as scientists are concerned, it's a process strictly for birds, sharks and dragons. And yet, human virgin birth underpins most of the world's major religions and is repeated in hoards of origins stories about great men. The virgin birth is central to the way in which we construct important men—men of genius—men who are so powerful, so pure that they are untainted by the sexuality of women.

Mary is, of course, the ur-virgin. A poor, young Jewish girl visited by an angel, chosen by an omnipotent god to bear his child. The pregnancy was meant to be a gift, a blessing for the blessed among women. But her purity also bore on her son—without a human father, the son of God was freed from original sin, born into perfection.

But Mary's blessing was not quite enough for later followers. A virgin birth alone wasn't nearly sufficient to secure her status as a woman worthy of adoration. So around the fourth century the Catholic Church began to support the concept of Mary's perpetual virginity. By the seventh century, the doctrine of the so-called "ever virgin" became central to Catholic liturgy. If her son could redeem all of mankind, then Mary's virginity could right the wrongs of Eve. Her purity could provide a redemptive path to sinful women.

The virgin birth is central to the way in which we construct important men: men of genius, men who are so powerful and so pure that they are untainted by the sexuality of women.

It's a doctrine born of a certain understanding of a woman's worth, one that understands that value as inherently paradoxical. To be in possession of virginity, but to bear a child; to be sexually untainted, but to be a mother; to be a subservient wife, yet to be chaste. It's an impossible standard against which to measure: the Virgin Mary's intactness is something to strive for yet never achieve. And it wasn't only the Catholic Church who offered this singular paradox as an example to women: Martin Luther affirmed the doctrine, as did John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist church.

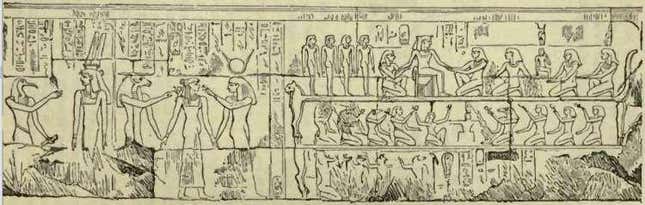

But the cultural longing for virgin birth is by no means the sole domain of Christianity. In Egypt, Queen Mautmes was visited by the ibis-headed Thoth, the messenger of the gods, and told that she would soon bear a son despite the fact that she was a virgin. Mautmes's virgin pregnancy was so revered that celebratory scenes were carved on the walls of Luxor Temple. There, she is escorted by both the holy spirit Kneph and the goddess Hathor to a cross symbolizing life; in the following scenes, she gives birth and her son Amen-hetep is enthroned. At his feet he receives the gifts of three men; he is worshipped.

A familiar story that long pre-dates Mary, Mautmes too was an ever virgin.

And there is Hera, queen of Olympus, who renewed her virginity every year in the holy waters of Kanathos. She spurned her adulterous husband (and the attention of mortal men), holding tightly to the moral authority that her virginity granted her. Hera scarified sex; in return she was rewarded with a son.

There is also Kausalya, the virgin mother of Rama, an avatar of Vishnu. There's the venerated Queen Maya of Nepal who, during a vision, was visited by a white elephant carrying a lotus in his trunk. The white elephant walked into her womb and reemerged on earth as the Buddha.

Virgins have given birth to the godheads of nearly every major religion. But it's a particular kind of motherhood: these mythical virgins never give birth to other women, and in the rare cases when they give birth to mortals, the men are far from ordinary. Genghis Khan was born to a virgin, stories say, as was Plato: he, according to Diogenes Laertius, was the son of Apollo.

Virgins have given birth to the godheads of nearly every major religion. It's a particular motherhood: these mythical virgins never give birth to other women.

Perhaps the most entertaining of virgin birth stories comes from the Greek biographer Plutarch who, hundreds of years after Alexander the Great's death, recounted the king's conception:

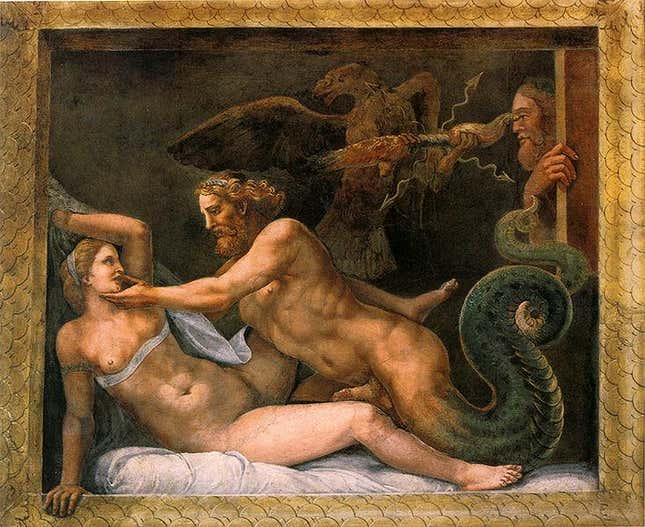

Before the night when her [Olympias, Alexander's mother] marriage with Philip was consummated, that there was a clap of thunder, that a bolt fell upon her womb, and that from the stroke a great fire was kindled, and then, breaking out in all directions into sparks, was quenched; then later, after the marriage, Philip saw himself in a dream placing a seal over his wife's womb; and the carving of the seal, as he thought, had the figure of a lion; and when the other seers viewed the vision with suspicion, as meaning that Philip should keep careful watch over things concerning his marriage, Aristander of Telmessus said that the woman was with child (since nothing that was empty required a seal) and that she would bring forth a son who would be high-spirited and like a lion in his nature. And so on one occasion there appeared also a serpent stretched out beside Olympias' body as she slept, and they say this especially dulled the love of Philip and his ardor so that he did not thereafter often approach her—either because he feared certain sorceries that might be practiced upon him, or because he avoided her on the ground that she belonged to one greater than he.

Whether or not the suggestively-named Olympias remained a perpetual virgin is unknown, Plutarch flirts at the suggestion with the "dulled love" of her husband who apparently found snakes and sorcery a turn-off. Other historians repeat Plutarch's story, though later embellishments make direct connections between Alexander's incarnation and his potent earthly power.

In one account, Olympias finally tells Alexander the secret of his birth right before he embarks on a military campaign. She suggests to her son that he show spirit worthy of such an origin. After all, she had endured claps of thunder and lightning bolts to her womb; conquering North Africa and Asia was the least he could do.

Virgin birth narratives are almost always triangular in structure: virginity makes you worthy of pregnancy, pregnancy is given as a reward, and the woman's value is both retained by her virginity and enriched by motherhood. Sex, too, is replaced with a series of metaphors: elephants, ibises, angels, bolts and claps. Conception, though always pleasureless, does not come quietly to the virgin mother—it is the primary event, so much so that it eclipses both the pain of birth and the nine months of gestation. (Because pregnancy and birth are the mundane labor of women, it's of little surprise that conception itself would be more valued, more important to mystical and miraculous narratives.)

Somehow, the value of women's virginity has hardly diminished since Mautmes was visited by an ibis-headed deity. Virginity still implies purity and innocence from sexual experiences and desire; it's still seen as a natural and necessary state for unmarried women. Think of how we utilize the language of virginity—a major life event, where body parts are broken or popped. We frame a singular sex act as an irrevocable loss; a violent subtraction of the whole rather than as a gain or addition.

And virginity is redemptive, but it's also regenerative. Think of poor Zebedee in her tank, swimming for the entertainment of wealthy tourists. Her biological anomalies are meant to repopulate an entire species, to restore a community that she thinks lost. In the 16th century, Hungarian countess Erzsebeth Bathory believed that she could preserve her beauty and her youth by bathing in the blood of virgins, who she sacrificed by the hundreds, slitting their throats and hanging them like animals in a butcher shop.

The virgin birth, despite its impossible paradoxes, is still very much with us. According to a recent longitudinal study published in the British Medical Journal, there were 45 virgin births reported in the United States between 1995 and 2008. Nearly .5% of the sample claimed divine intervention, not sex, as the source of their pregnancy. It's an astonishing statistic, one that speaks to the way in which mythological narratives continue to mold women's sexuality. Most of the women who claimed virgin births were from deeply religious households and had signed a chastity pledge. They were also unmarried.

It seems astonishing that, in the 20th and 21st centuries, that women would choose to cleave to the myth of virgin birth rather than simply acknowledge that a pregnancy was the result of out of wedlock sex. But maybe it's not. A married mother seems to retain something of virginity's purity. It's why Kim Kardashian could be publicly scolded for posing nude. "You're someone's mother," wrote Naya Rivera, a familiar chorus meant to hem in the sexual acts of women who are meant to shed their sexuality once a child arrives, to robe themselves in the blue of the sweet Virgin Mary. And it's why single mothers—particularly women of color—are marked as degenerates. Single fathers are heroic; single mothers are fodder for presidential debates because their sexuality is publicly owned, their children marked by the sin from which they were born.

It might be easy to scoff at women who would still proclaim their pregnancies to be the result of divine intervention, to roll our eyes and advocate for broader more accessible sex education. But perhaps those 45 women were onto something; perhaps they understood that people would rather take the Virgin Mary in all her impossibilities than the single mother, who instead of being honored is marked.

Stassa Edwards is a freelance writer and editor.

Top image by Jim Cooke. Images in text: Birth of Christ in the Cornaro Missal, c. 1600; Annunciation Scene, Luxor Temple; Giulio Romano, Jupiter and Olympias, Fresco in the Palazzo del Te, 1526-1534

Additional Reading:

Hanne Blank, Virgin: The Untouched History, 2008

Laura Carpenter, "Gender and the Meaning and Experience of Virginity Loss in the Contemporary United States," Gender and Society, 2002

Aarathi Prasad, Like a Virgin: How Science is Redesigning the Rules of Sex, 2012