Like so many young girls, I saw Disney’s The Little Mermaid and was entranced. I spent hours at the pool trying to perfect my “part of your world” hair flip. Now I am 33, and I watch my four-year-old daughter do the same thing, dipping under water and flipping her long blonde hair over and over, bobbing between air and water. Her joy lies in that place between.

“I’m being a mermaid!” she yells to me. I try to tell her I did the same thing when I was little, but she doesn’t hear me, too busy pretending. She’s never been adventurous on land. She didn’t walk until she was 18 months old and still sobs in terror at tall slides. Even now, her three-year-old brother can scale higher heights than she can. But the water has always been her home. She will endlessly ride the highest waterslide with her father, crying only when the life guards refuse her requests to ride alone.

“She’s a great swimmer,” her swim teacher tells me.

“She’s part mermaid,” I joke, sometimes feeling like I’m not joking. I don’t believe mermaids are real, but like I tell my children, I don’t like to rule anything out conclusively.

Sometimes, it must be said, mermaids are men. But most often they are women, and they are almost culturally universal: known as sirens, water spirits, selkies, ceags, they exist in the ubiquitous waters of our imaginations, and within our imaginations, under the churning sea. Complicated, fishy, witchy women, both lucky and unlucky. They save men and they destroy them; they make wonderful lovers and terrible wives. Samuel Butler wrote in Hudibras:

Alas! What perils do environ/ That man who meddles with a siren!

Despite the lack of credible evidence for mermaids, the myths persist. There has been so much confusion that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) had to issue a statement on the matter, which declared, rather tersely, “No evidence of aquatic humanoids has ever been found. Why, then, do they occupy the collective unconscious of nearly all seafaring peoples? That’s a question best left to historians, philosophers, and anthropologists.”

So, let’s begin.

The history of mermaids begins with the ancient Syrians, who worshipped the goddess Atergatis. The goddess of fertility, she was often depicted with a fish body, although the mythologies surrounding her describe her as anthropomorphic. From Atergatis, the myths multiply and can be found in almost every culture and on every continent.

Mami Wata is an African water spirit, often pictured as a mermaid. She has healing powers and brings good luck, but she also drowns those who displease her. In some traditions, Mami Wata is alluring, beckoning men into her depths under the guise of a prostitute, then revealing herself to them in the sticky aftermath of sex. She then demands absolute fidelity and secrecy. To please her is to have good fortune and to cross her is to find your death in her murky folds.

In the Caribbean Islands and parts of South America, there is a similar legend: Lasiren, who holds a mirror, the backside of which leads to her dark watery world. According to legend, Voodoo priestesses are made by descending into the water with Lasiren and reemerging imbued with her powers—a female baptism into the depths of the yawning ocean. In Haiti, Lasiren is one of three sisters. One sister is calm. The other is hot-tempered. Lasiren embodies both attributes, and together the three of them form a twisted cord of female stereotypes.

The Greeks saw mermaids too. Odysseus had his men tie him to the front of his boat, so he would not be swayed by the aquatic sirens’ dangerous calls. A popular Greek folktale claimed that Alexander the Great’s sister Thessalonike was turned into a mermaid who haunted the Aegean Sea. She would accost sailors and ask them, “Is King Alexander alive?” If they said yes, then she would calm the seas. If they told her no, she would stir up a terrible storm. In Midsummer Night’s Dream, Oberon tells Puck that he once saw a mermaid riding on a dolphin’s back, singing a song that caused the sea to grow calm: “And certain stars shot madly from their spheres/ to hear the sea-maid’s music.”

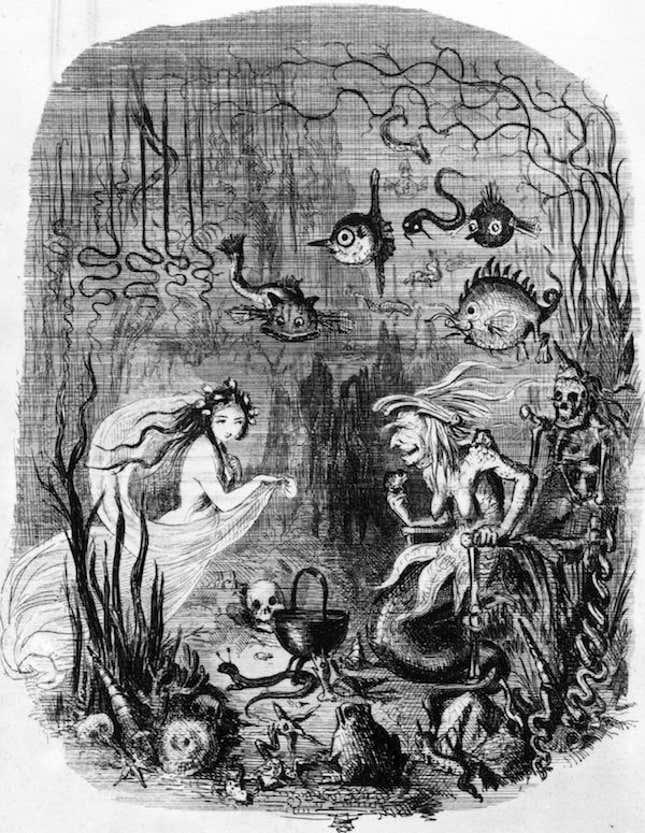

Hans Christian Andersen wrote a tragic tale of a mermaid who fell in love with a human man, lost her tongue and turned into sea foam when she refused to kill him in order to regain her original form. As her body bubbles into foam, the mermaid discovers that she has become a daughter of the air, who must win her eternal soul by performing good deeds for 300 years. (Disney later bowdlerized this story into a children’s movie.) Christopher Columbus saw a mermaid, or so he wrote in his journal. (It was a manatee.) So did Henry Hudson and John Smith, who felt the “first pangs of love,” and noted that the creature, with her long green hair, was “not unattractive.”

In Eastern European legends, mermaids are the lost souls of girls who committed suicide or who were murdered. These water ghosts of the unclean dead call men to their death, luring them with their flowing green hair. In Japanese legends, mermaids cannot speak at all, and they cry tears of pearls.

Not all stories of mermaids are quite so gilded with myth. In his credulous book The Mystery and Lore of Monsters, CJS Thompson tells of a mermaid who fell through a breach in a dyke at Edam in Holland, and subsequently learns to become a good housewife and Roman Catholic from a kindly Dutchwoman. This story mirrors the tales told about quasi-domesticated selkies—half seal, half human—who were rumored to be the perfect partners, if only you could catch one and steal their seal skin. But if the selkie partner ever found their skin again, they would leave you forever with your half-breed children and return to the depths.

Tennyson depicts a mermaid in Confessions of a Mermaid as a vain creature who contemplates her beauty in a mirror. In his poem, the mermaid speaks:

I would comb my hair till my ringlets would fall

Low adown, low adown,

From under my starry sea-bud crown

Low adown, and around

And I should look like a fountain of gold

Springing alone,

With a shrill inner sound,

Over the throne

In the midst of the hall.

Like Lasiren, her world is seen through a mirror. But unlike Lasiren, this mermaid is trapped there, in the prism of her own reflection. Everything is refracted through the glass of the mirror, like the glass of the water. Everything is within sight and yet unknown. And maybe this is why it is always mainly women who are caught in the water. Men inhabit what can be conquered and colonized; women fit easier in the sea, a space of danger and separation.

Bearing the weight of a hundred known myths but the fact of being unknown in reality, mermaids that are “found” tend to represent a horrifying amalgamation. The most famous “captured” mermaid is the Feejee mermaid, of which there were several, all fakes. They originated from Japan, where they were used in religious ceremonies before being discovered by merchants and sold off to sailors.

The most famous Feejee mermaid was found by an American captain, Samuel Barrett Eades. Eades bought the mermaid from Dutch merchants, who claimed to have bought it from Japanese fishermen, who reportedly caught it in their nets. According to Jan Bondeson in his book The Feejee Mermaid and Other Tales Eades sold the ship he was sailing for $6,000 in order to buy the mermaid. Steven C. Levi tells another story in PT Barnum and the Feejee Mermaid: that Eades borrowed the money from from the ship’s expense account. In any case, neither the ship nor its capital belonged to Eades, and the ship’s owner, Stephen Ellery, was not happy to have his metaphorical cow sold for some magic beans. Ellery sued Eades and had the mermaid declared a Ward Chancery, or ward of the court, in order to prevent Eades from fleeing the country with the precious lady. Eades was ordered to pay back the $6,000, but he never did. He sailed the seas for 20 more years to pay off his debt, making his fake mermaid a truly bad investment: an unlucky curse of the utterly non-mythological sort.

This Feejee mermaid was probably nothing more than a monkey torso and head, attached to a fish. It looked nothing like the romanticized depictions written down by sailors and poets throughout the centuries. A journalist from the Charleston Corrier, who saw the mermaid years later when she toured with Barnum, wrote, “Of one allusion... the sight of the wonder has forever robbed us—we shall never again discourse, even in poesy, of mermaid beauty, nor woo a mermaid even in our dreams—for the Feejee lady is the very incarnation of ugliness.” In photos, you can see the fish tail affixed to the dried carcass of a human-like animal; sometimes the long withered breasts are visible, always, the face of frozen horror—as if she had died in shock and revulsion at the stupidity of men.

The mermaid was passed down from Eades to his son, who sold her to Moses Kimball, who leased her to PT Barnum, who turned her into a sensation, profited, and then lost her.

The gullibility of the hordes of the past, flocking to see the shriveled and shrunken mermaid, could be attributed to a simple lack of scientific knowledge. But there were skeptics, even then. It didn’t matter. People believed in her regardless. Even Eades is reported to have gone to his grave defending his shriveled half-girl.

Additionally, belief in mermaids is not something that belongs to mythologies past. In 2013, Animal Planet aired a documentary that claimed mermaids were real and there was credible evidence proving their existence. A brief disclaimer at the end of the film stated that the documentary was fictitious, but plenty of people took the documentary at face (or fin) value and stormed social media with their proclamations of belief. Watching it, it’s not hard to see why people were duped. The fake scientist in the fake documentary says very convincingly at the beginning of the show, “…The surface of the moon has been explored more than the deep ocean. And you look at the fact that to this day there are large animals still being discovered. There have been two new species of whales discovered in the past decade. These are 30-foot, 40-foot long animals that have never been seen before. Seen for the first time ever in just the past ten years. So yeah, it’s possible, it’s still possible to stay hidden.”

This documentary was in part what inspired NOAA to release their statement. And the answer to the question they pose, why mermaids persist, is complicated. There has to be some physical foundation to base this recurring, persistent myth.

Some scientists believe that stories of selkies and mermaids were inspired by accounts of skin diseases and rashes. In fact, hyperkeratosis, a skin condition that is marked by an unusually thick outer layer of skin, is often called “The Mermaid’s Curse.” One family on a remote Scottish island has lived under this curse for years. Thompson tells of boy who was born in Italy in 1684, “quite covered with the scales of fishes, having nevertheless a beautiful and comely neck and face with no unseemly color.” Like a bad rash, these “scales” later fell off the boy.

Others believe that sightings of mermaids were inspired by glimpses of manatees and dugongs. Although, as Bondeson writes, “The only objection to this theory is that it would take a half-delirious sailor to mistake the features, or rather lack of features, of the dugong with the face of a beautiful mermaid, or to hear the siren’s song in the snuffling sounds made by these ungainly beasts.”

In looking for an answer, I feel like just another sailor, staring into the dark face of the ocean. Oceans cover almost three-quarters of the earth’s surface but remain a mystery: a watery stranger that lives beside us. We see it often and we know so little of it. We do know, however, that it must be capable of anything. And we know how, when our eyes see something we don’t understand, our minds, influenced by stories, legends, and sublimated desire, fill in the rest.

And, even more so than the ocean, the territory most open for wrongful interpretation—the most known and yet unknown—is the female body. What issues forth from us is still a mystery to people who see only their sublimated desires reflected back at them. Mermaids—the woman in the ocean, her lower parts unknown—represent an over-familiar narrative in history, of men thinking they know women, then actually knowing nothing at all. Bodies of women have been the subject of art for millennia, yet few men can tell you the difference between the vulva and the labia. The existence of the clitoris has been debated for years. (Unlike the mermaid: it exists!)

We ourselves, as women, are no strangers to confusion and ambivalence about our own territory. What’s beautiful is dangerous; what’s attractive is disgusting; what’s magic contains pain. Perhaps this explains why the myth of mermaids has yet to die off. Even women embrace this mythology—I do, in my own way.

And through my daughter, I see a glimmer of an answer to the question that baffled NOAA. Perhaps as women don’t feel like we really belong here. This world of men, isn’t ours. How much easier it is to believe we are transformed creatures, walking an earth that is unknown to us. We are cursed with our legs. On land, we have no voice. But down in the water, we are suddenly free. There is a place yet uncolonized, where the danger belongs to, is perpetuated, by us.

Lyz’s writing has been published in the New York Times Motherlode, the Washington Post, LitHub, Aeon, Pacific Standard, and others. She is a contributing writer for the Daily Dot and skulks about on Twitter @lyzl.