After I bought a cabin in the woods last year, I realized there were many things about living in the woods that I, a child of south Texas who then promptly decamped to the paved and well-lit streets of New York City, needed to learn. For instance, how does one turn large pieces of wood into smaller pieces of wood? I had purchased a quarter-cord of wood for the winter, but many of the logs were too big to fit comfortably in my wood stove, and it was cold.

So I searched “how to chop wood,” and lo and behold, Google delivered to me a video, helpfully titled “How to Split Wood,” by a website that was new to me but not, apparently, to millions of men—the Art of Manliness, which has existed for more than a decade and describes itself as “a men’s interest and lifestyle website with content geared to helping men become better men.” Are you even a man in today’s modern world, full of conveniences like pre-chopped wood in the size you require, if you don’t chop your own wood? Of course not, what a silly question.

I learned many things from the video, namely, that I needed something called a maul and not an ax as I had assumed, and that chopping wood was also a “great workout.”

What I did not learn, unfortunately, was how to successfully chop wood:

Even though I had failed at the art of manliness, it got me curious about the Art of Manliness, whose Mormon founders Brett McKay and his wife Kate, I soon learned, had built a mini-empire around the belief that men were on the decline and increasingly useless, lacking ambition and drive especially when compared to women. “These men who are struggling are your sons, they’re your grandsons, they’re your brothers, they’re your potential husbands,” Brett explained in a 2011 talk he gave in which he laid out his manifesto, blaming a whole slew of ills for men’s struggles—“absent dads,” “pop culture,” consumerism (which had made men “passive” and “weak”), as well as feminism, which had left men “lost and confused” about what it meant to be a man. Feminism had led to the idea that masculinity needed to be reinvented, which he interpreted as the desire to have “men act more like women.” “We don’t need to reinvent masculinity in America,” he proclaimed, we just need to “revive the rich heritage of manliness,” which has a history that “goes back thousands of years” all the way to the ancient Romans.

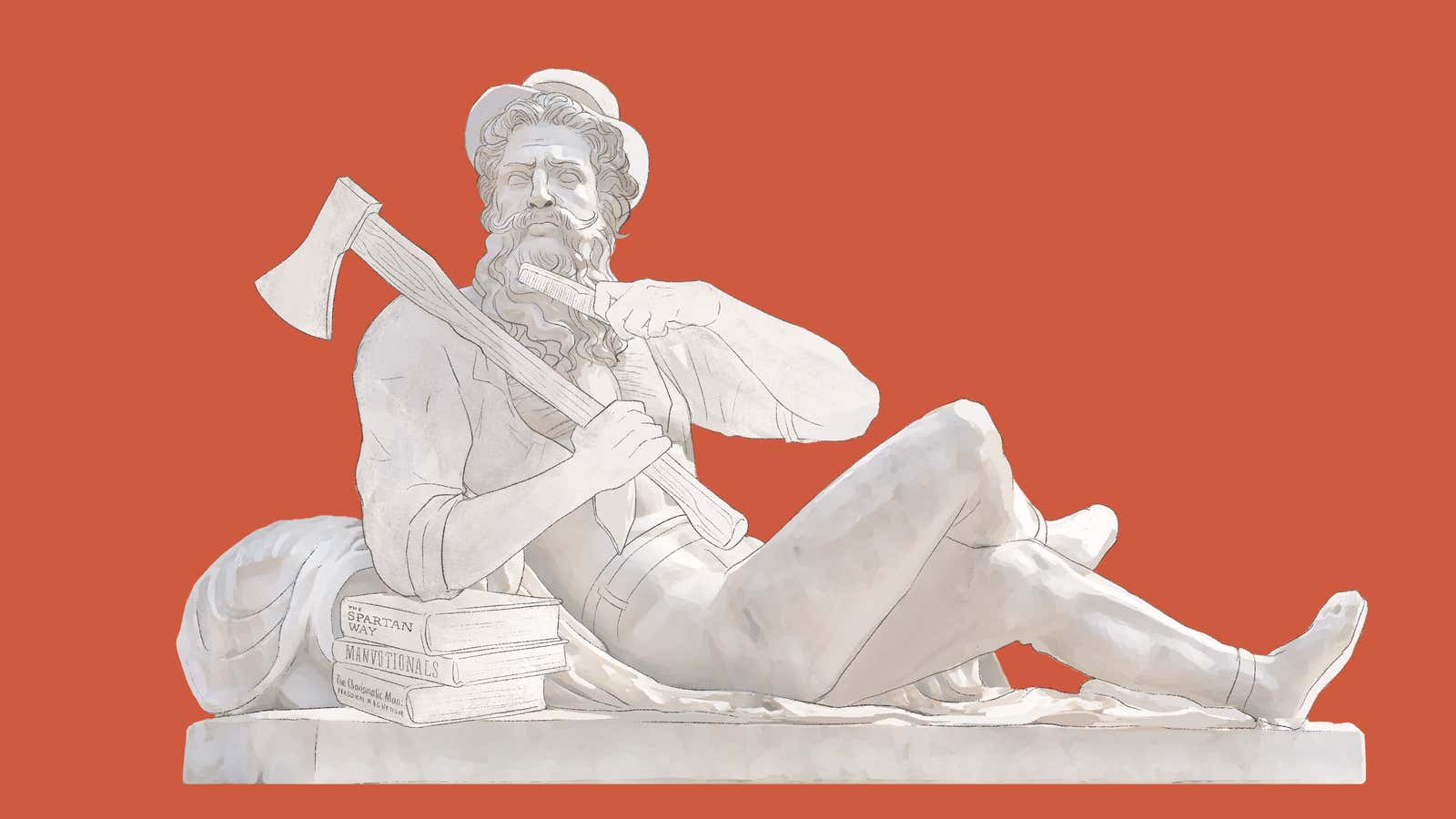

It’s a conservative ideology, a sort of Jordan Peterson-light and with more than a nod to the ideas that drove the mythopoetic men’s movement of the 1980s and books like King, Warrior, Magician, Lover, which is cited in their introduction, and the poet Robert Bly’s Iron John, both of which fretted that men were crushed by modern society and no longer wild. It’s an ideology that still resonates today—in 2019, the Art of Manliness averaged more than six million monthly visitors, according to Tulsa World. The brand has millions of followers across its social channels, and since its founding the McKays have expanded their company into a veritable conglomerate of manliness; in addition to a podcast and a series of books, the Art of Manliness also offers a 12-week training program called the “Strenuous Life.” Akin to the Boy Scouts and complete with badges, the Strenuous Life is marketed as an “initiation into the cult of strenuosity” for adult men who want to “revolt against our age of ease, comfort, and existential weightlessnes” and “connect with the real world” and “stretch themselves and do hard things.” (Participants can gain a First Aid Badge, as Strenuous Lifer @grekulanssi did, by carrying their wives like a firefighter.)

Having gotten its start at a time when pundits and glossy magazines began bemoaning and warning of “the end of men,” the Art of Manliness yearns for a return to a more secure time when to be a man was to be the sole breadwinner in his (nuclear) family, and squarely at the top of both their private and public domains. This limiting version of what a man should be isn’t as overtly boorish and violent as the set of beliefs espoused by, say, the Proud Boys, or as misogynistic as those embraced by incel culture. But it tracks closely with masculine ideals that have long been embraced and valorized by the right, not least of which the idea that there is some sort of singular Platonic ideal of manhood that men should aspire to.

Is there any insight to be gleaned about being a man in 2020 from the Art of Manliness? Somewhere, in the hundreds of podcasts, thousands of blog posts, and the seemingly endless scroll of videos, maybe there would be some answers.

So what the hell is manliness? In the McKays’s 2011 book, the clunkily titled The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues, they break down how to “master the art of manliness.” A man, they write, “must live the seven manly virtues,” the first of which is, amazingly enough, “Manliness” (!!!), followed by “Courage, Industry, Resolution, Self-Reliance, Discipline, [and] Honor.” Men, they believe, want to “live an authentic, manly life,” to “live life to the fullest.”

Still confused about what “manliness” is? There’s this blog, helpfully titled “What is Manliness?” In it, Brett writes that “manliness” is:

striving for excellence and virtue in all areas of your life, fulfilling your potential as a man, and being the absolute best brother, friend, husband, father and citizen you can be.

Women can be “virtuous” too, Brett writes, but in a different way, because, of course, women are inherently different from men:

Which is to say that women and men strive for the same virtues, but often attain them and express them in different ways. The virtues will be lived and manifested differently in the lives of sisters, mothers, and wives than in brothers, husbands, and fathers. Two different musical instruments, playing the exact same notes, will produce two different sounds. The difference in the sounds is one of those ineffable things that’s hard to describe with words, but easy to discern. Neither instrument is better than the other; in the hands of the diligent and dedicated, each instrument plays music which fills the spirit and adds beauty to the world.

“The bottom line?” McKay writes. “True manhood still exists for those who seek it,” on websites, naturally, like the Art of Manliness.

The Art of Manliness often reads like a lifestyle blog, full of sartorial tips and hair styling recommendations, an eHow but solely for men on how to be men. The very first post shared by Brett in 2008 taught someone “how to shave like your grandpa,” a rather shallow encapsulation of McKay’s belief that men should “move forward by looking back.” “Proper shaving has become a lost art,” he bemoaned, before extolling the benefits of the “fine art of the traditional wet shave.” A wet shave, he wrote, would make a man “feel like a bad ass,” like JFK and Teddy Roosevelt. There are more than two dozen blogs on the Art of Manliness website about shaving alone, a nod to the kind of lifestyle content that I suspect leads many to find the site for the first time. It’s how I found the site, after all, merely needing a tutorial on how to chop wood.

But “true manhood,” as it was in the good old days, seems to only be available to straight, heteronormative men. There are, according to the Art of Manliness, merely “3 P’s of Manhood”—protect, procreate, and provide, which form the basis of “Manhood 101.” (Search “LGBT” on their website, and you’ll get a blank page with no results.)

What else do real men know, other than how to “protect, procreate, and provide?” Men know how to tie a tie. They know how to write a letter. They know how to dry wet boots with hot rocks. They agree that every man should be strong. They know that broad shoulders, aka “man antlers,” attract women. They know how to make a leather belt. They yearn to go through a rite of passage from boyhood to manhood. They know the importance of developing a strong he-man voice by using the voice nature gave them.

Today’s men, sadly, aren’t taught these necessary skills, the site posits—not by their fathers, nor their grandfathers, or society at large, hence the scourge of men never learning to be men. What I find ultimately telling about the Art of Manliness is its recasting of self-help, typically seen as a feminized endeavor, into one for the manliest of men. Brett even nods to the self-help nature of his and his wife’s project when he talks about the origin story of their website:

In 2008, Brett McKay was in a now-defunct Borders bookstore on 81st Street and riffling through men’s magazines when he realized he just didn’t connect to the content.

He’s a married man; articles about hooking up, washboard abs, drinking and eye candy felt tailored to a different demographic.

So he began scrawling in a Moleskine notebook ideas for the sort of content he wanted to read, crafting a more wholesome and classic ideal of a men’s magazine.

Kate, his wife and business partner, also spoke of their shared belief in the need for a new kind of men’s self-help guide. “There’ve been a lot of articles these days [asking], ‘What’s happening with men? Is there a place for men in modern society?’” Kate told BYU Magazine. “A lot of people out there are feeling sort of lost: they don’t have a sense of purpose in their life, don’t know how to live. They’re really hungry for this kind of knowledge—how to improve themselves, how to be a good person.”

But what permeates through the Art of Manliness is less a desire to be a “good person” than the rarely unacknowledged anxiety and insecurity drawing readers in the first place. After all, the flipside of wanting to learn to be a man is the belief that you’re inadequate as you are. If a deep, misguided anxiety is baked into conservative fretting about men and is then projected out into our political life, the Art of Manliness largely turns it inward, into an aesthetic one that can be papered over with the right look and the right activities. And while learning how to tie a tie or chopping wood may be a useful life skill, the ultimate lesson from the Art of Manliness is this—that masculinity is just, at the end of the day, a performance of a series of tricks. Maybe that’s the manliest thing about it.