It was a remarkably odd feeling to sit slumped over in an office arm chair, my coworkers watching me as I described my own death.

Overseeing me as I told a story so personal that until that moment I didn’t know it existed was Ann Barham, LMFT, a certified past life therapist who attempts to help people heal their present by digging into pasts so far back that they end up in a different lifetime. Using methods of hypnosis and meditation, she acts as a guide through her clients’ former lifetimes—or, for skeptics, the “deep psyche”—to unearth buried sources of anxiety or pain. Last year, she published her first book, The Past Life Perspective, which details her work and the emotional discoveries her clients have made.

This was my first time meeting Barham, but it was not my first time seeing her. I had written about her once before when she appeared on a talkshow late last year, demonstrating past life regression on one of the Real Housewives. To be frank, I wasn’t particularly kind in my write up of the segment. As I put it at the time, “It’s all bullshit, anyway.”

But bromidic though it may be, since turning 30, I’ve become more and more intent on exploring what scares me and better understanding my own paradoxical spirituality: For example, I don’t believe in an afterlife, yet I’m terrified of ghosts; I joke about horoscopes and astrology, but still try to avoid signing important paperwork while Mercury is in retrograde; I put my faith in science, but lack the certainty or courage to commit fully to atheism. In that vein, I do not reject the notion of past lives outright. Growing up, my family—not exactly new age, but not exactly not—discussed the concept frequently. My parents visited a past-life channeler when I was a child. The channeler then told my step father that power was very important to me and that I don’t do well when it’s taken away, an insight that turned out to be invaluable to him as I adapted to living with someone who was not my biological father. (He still partially credits it for our closeness and good relationship to this day.) But despite a strong familiarity, I’m still reluctant to believe anything until I experience it myself.

Which, indeed, I was about to do.

Before we met, Barham asked what I wanted from our time together. I could choose an issue ranging from an inexplicable phobia to chronic undiagnosable pain to an aversion to commitment. Some who experience foot pain regress to lives where their feet were broken and bound. A person with a fear of water might have drowned at sea. Daunted but eager, I wrote to her with my choice: to explore the social anxiety that has plagued me since puberty, something I’ve spent years working through in traditional therapy with mixed success.

I was nervous about the actual session for a multitude of reasons. In light of my former coverage of Barham’s work, I felt slightly sheepish encountering her in person. More pressing, though, was my worry that nothing would happen during our appointment and it would be a waste of Barham’s and my time. I also feared that too much might happen, and I’d look like an easy mark to our audience—not only in writing, but because we agreed to film it, also on camera. The public nature of our session aside, these were normal worries, Barham assured me—as was my sideline, but serious fear that I’d regress to a life as a Nazi or someone equally shameful that I’d have to share with the world. It happens often—an anecdote in her book described a client who (to his horror) revisited a life as a soldier in the S.S.—but that’s to be expected. It’s hard to live dozens of lifetimes without hurting a tremendous amount of people along the way.

As for my appearing duped, past life regression therapists often cite the Jungian concept of synchronicity, the “acausal connection of two or more psychic and physical phenomena” or, in layman’s terms, the psychological profundity of coincidence. In The Past Life Perspective: Barham writes:

Occasionally, clients worry after the regression that maybe they “just made it up” or it was only their imagination. In the scheme of things, that isn’t particularly important. In the first place, we can treat the past life stories as illustrative metaphors for the issues and influences in a person’s current life. It gives us very rich material to work with, as any therapist who employs dream interpretation, creative imagery, sand tray work, or other projective techniques well knows.”

In other words, whatever I was to experience would not be a result of my own susceptibility or gullibility. Rather it would reveal something, perhaps not a real past life, but maybe a symbolic figment of the imagination that could speak to my underlying anxieties. Past life regression therapists commonly fall back on synchronicity when confronted by those who doubt their methodology or the usefulness of their work, though whether or not it’s a satisfying answer is entirely subjective.

Barham arrived at our studio harried after a miscommunication had sent her scrambling around lower Manhattan in the summer heat. A petite woman with a pleasantly raspy voice that doesn’t immediately recommend itself to hypnosis, she shifted quickly from mildly annoyed to therapist mode, her energy now calm and contagious. Arranging her supplies, a tape recorder and a bottle of water, she spoke with me briefly about what would happen over the next two hours. She would hypnotize me, but not to the point where I’d lose self awareness. Instead, I’d be in a liminal state: one foot in the present and the other in the past. Throat lozenge clicking occasionally against her teeth, she told me to remove my shoes and get comfortable.

Sinking low in a stiff office armchair —so low that, to those watching, I surely looked like a human puddle—because we didn’t have the couch required for me to fully lie down as Barham requests, I slipped on the offered eye mask and submerged myself in utter darkness as she began coaching me into a deep meditation and more vulnerable psychological state.

“Ten.” She began to count backwards. “Letting go of all your worries. Nine. Know that nothing can harm you right now. Eight. Deeper and deeper.”

Unlike a mystic or psychic who would dictate your experience to you, Barham is there only as a sounding board and compass, encouraging you to follow your instincts and trust your brain to guide you where (and when) it needs to go. If you end up in a past life, you got there yourself. Past patients have revisited lives as monks in Medici Florence, prisoners in 1580s Spain, housewives in northern India, and soldiers in Vietnam. (Contrary to what clients might hope or expect, it is incredibly rare for a person to experience life as a famous person and most people, according to Barham, have never been particularly noteworthy across the entirety of their lifetimes.)

Even under hypnosis as I now was, I found it hard to trust myself to narrate a sincere and meaningful experience as it appeared. But in my relaxed (and drooling) state, I forced myself to answer Barham’s questions with whatever first came to mind and rang true (sometimes, admittedly, there was nothing there). Her first question, a practical one, took a moment to answer. I was supposed to look down and imagine the shoes of the person I once was. (Footwear—or lack of—is an apparently excellent indicator of time, place, and social status.) After a seconds of concentration, I brought forward the image of dusty leather lace-up boots, caked in desert grit, and suddenly—in pleasant defiance of my previous worries—I couldn’t stop foreign imagery and sensations from racing through my brain.

Not all people participating in past life regression experience, as Barham describes, “a 3D IMAX movie” of another lifetime. Some enter the regression in more subtle ways—through scent and sound, for example. My first sensation was intense dizziness, as though the world was spinning, even though in reality I was half asleep in my stable armchair. The world refused to right itself as I tried my bearings and once it finally did, I found myself alone in a canvas tent lit by flickering gas lamps. I was sweating profusely, and I was dying.

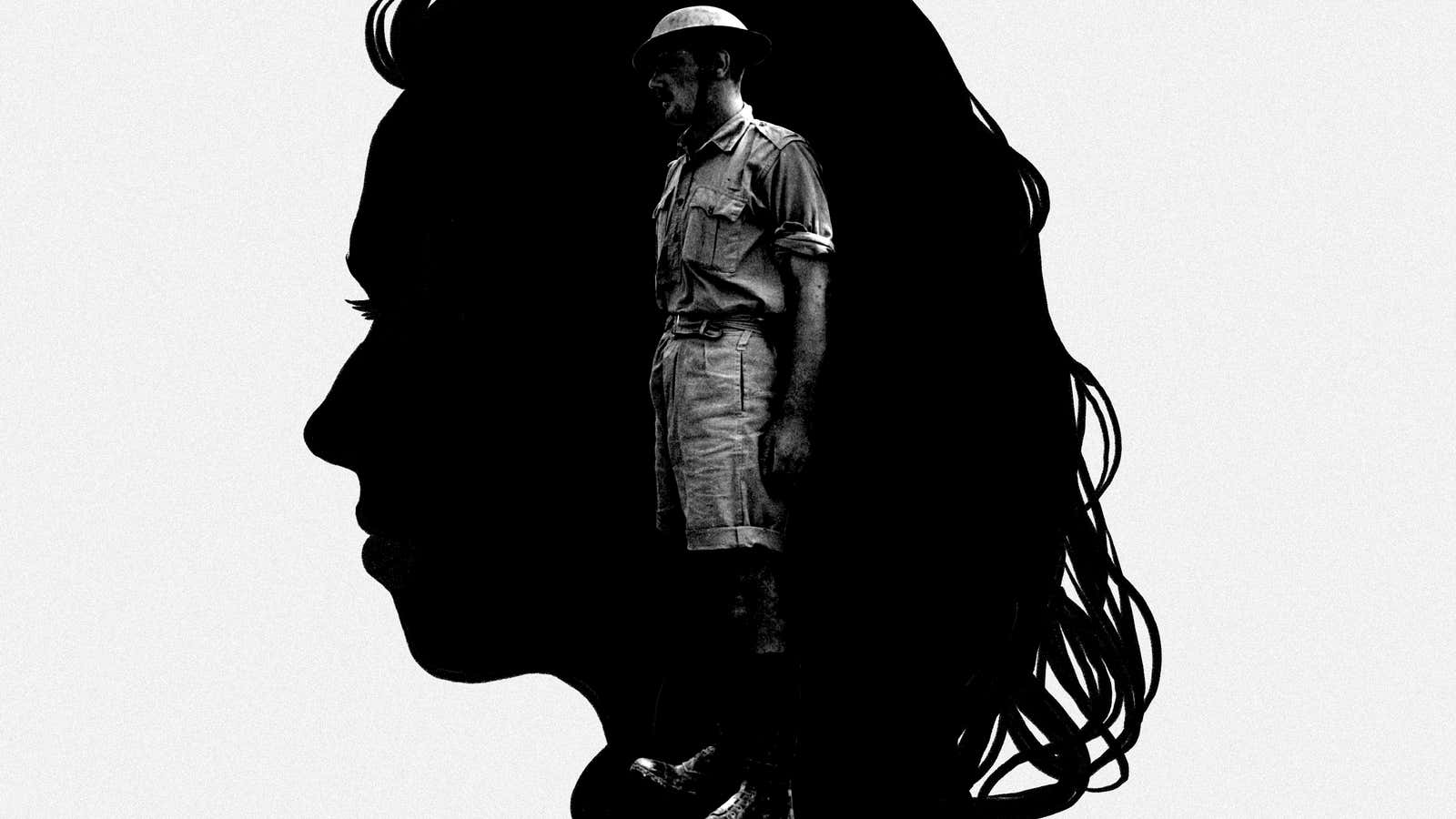

As she does with all clients who immediately experience something traumatic in their regression, Barham responded to my observations by asking me to pull back from the moment slightly and learn whose lifetime this was and what had led the former me into those particular circumstance. Again trying to answer with whatever felt right, I introduced myself as a high ranking male British soldier stationed in the desert during the race to colonize Africa in the late 1800s. (So not a Nazi, but not entirely far off.) Cocky and surging with affection for Queen and Country, I felt free, not plagued with self-doubt or guilt (even deserved guilt) for quite possibly the first time ever.

But what about “my” family, Barham wanted to know. Here, I found myself remembering a well-appointed summer manor house, a doting mother, and a stoic and studious older father. Asked if I spiritually recognized them as anyone I know in my current life, I saw my current father in the mother’s kind and loving spirit—in her movements and her the way she interacted with “me,” her young British son. Before the past me went off to boarding school and then the military academy (all seen in flashes, like a montage), she homeschooled me, making our lessons silly and entertaining as the father was away on business or in his study working. I immediately recognized my current mother as my best friend in the British Army, someone with whom I was dispatched to Tunisia, Egypt and Morocco, and towards whom I felt an undeniable and seemingly immortal companionship.

Following these revelations, Barham guided my visions back to the tent, to the dizziness, to the dying. Now that I had a clearer picture of this person whose body I was inhabiting, what—she wanted to know—gave this moment its particular significance?

In a voice flatter than my own, I informed her that I was ill from malaria and had told my regiment to go on our expedition without me, retrieving me upon their return. Secretly, though, I knew that I was dying and would needlessly slow them down. Asked by Barham if I had any regrets or felt guilty about not fulfilling my duty, the answer was no. The deep sadness I felt was that of missing out, of missing my friends and the adventures we were supposed to have together. And I didn’t want to die in the tent. Somehow I managed to crawl out into the sand and look up at the stars as I drew my last breath. Feeling a warmth in my chest, like my heart had melted into a million tiny universes, I told myself that if this was death, there was little to fear. Once again, in my current and actual body, the one that was seated in the armchair, I found myself crying.

Slowly then, Barham brought me out of my hypnotic state; I removed the eye mask and wiped the tears from my eyes. It was interesting, she noted, that I wanted to find the root of my social anxiety and instead experienced a life in which I had none. Perhaps, she speculated, this was my brain or spirit’s way of telling me that there can be comfort and safety among others.

There was power in what I experienced while under hypnosis. Feeling remarkably light after she and I said goodbye, I called my parents and told them what I had done. If reincarnation was real, I wanted them to know how deeply happy I was to keep experiencing life with them. If it was all a figment of my imagination, I noted, they should still feel touched that my brain chose to cast them in such significant roles.

But while I found reassurance in Barham’s interpretation of the regression, and repeated everything to my parents with verklempt enthusiasm, very little time passed before I began to doubt all that I had seen or heard while under hypnosis. While there’s comfort and beauty in the concept that our loved ones follow us from one lifetime to another, and I long for it. (Though this also strikes me as a tactic our brains throw at us mid-regression to ease our fears of dying.) Indeed, recognizing the spirit or essence of someone you know is a frequent occurrence in past life regression. In her book, Barham writes:

From everything I have learned as a past life therapist, we tend to travel in groups. Most people in the field refer to a “soul group,” a group of souls with whom we have a strong connection and with whom we choose to reincarnate into a similar time and place so we can be together on the human plane. Usually, this is because of a strong love connection. At times we may find that these are the individuals who also challenge us the most; most likely we have agreed on a soul level to come together and work out negative dynamics or to help each other with important areas of personal growth.

The idea that we travel across lifetimes with the people we love is an alluring concept because it supposes that death is almost usually a temporary parting, and only rarely a goodbye. No wonder people—especially those who’ve experienced or fear loss—find comfort in it. I welled up underneath my eye mask (not for the last time) upon recognizing my family and felt my heart swell at the notion that I was with them, in some way or another, always. Even across lifespans.

Or maybe I wasn’t. One of the chief skeptical speculations about past life regression therapy is that what’s experienced while under hypnosis is the result of cryptomnesia, the accidental plagiarism of books, TV, movies, or stories. Considering my own regression, I can certainly find enough pieces of The English Patient or The Lost City of Z (or even the survey of Africa course that I took in college) to create an exciting story. Another possibility, as some in the psychiatric community speculate, is that what I went through was the result of confabulation—the creation of false memories—a phenomenon often associated with recovered-memory therapy, a highly controversial technique that, while meant to recover memories from the past, has, on occasion, planted false (and often traumatic) memories in the patient’s mind.

As for the standing of past life regression therapy in the psychiatric and therapeutic communities, Dr. Brian Weiss—the preeminent past life regression therapist in the United States and Barham’s mentor—was according to the New York Times, “censured by the medical establishment” after publishing his book Many Lives, Many Masters in 1988. At present, mental health professionals remain divided. Many licensed and fully-qualified marriage and family therapists (including Barham herself) find it a useful tool. But in possibly greater numbers, many dismiss it out of hand. As my regular psychiatrist—someone I trust deeply—dryly stated, my session “must have been a nice fantasy for you.”

And it was.

I found myself impressed with the exceptional power of the human brain—my human brain!—and its ability to produce a (very gripping, if I do say so myself) story of that magnitude, seemingly out of scraps and pieces of long forgotten ephemera. My imagination was able to produce a sense of emotional freedom and solace that I’ve since been able to revisit, and it’s been useful—whether it’s based in reality or not. White, male confidence (or at least my imagination’s perception of it), for example, is something we should all get to experience at some point or another. It’s true that I rarely recommend replicating anything a white man does, but to walk through a situation and not question your adequacy along the way does indeed do wonder for your self worth.

I’ve also been left with an immense gratitude for the people in my life, whether or not they’re present in lives past and future. And for my current life in general. What would a future me think if they were hypnotized back to 2017? My gut tells me that they would be encouraged by the community I’ve cultivated and the work that I do (more than I can say for the British colonialist). But that is, or should be, irrelevant. We are here now, in this lifetime, experiencing moments as they come. We do not know what will come next and it is that—not the past—that makes life more terrifying and invigorating. I will try to savor rather than escape it, but it’s good to know that when needed, a different life is but a hypnosis away.