On March 11, 2020, I was slumped on the sofa, scrolling through Twitter, reading strangers’ jokes, thoughts, and nervous prayers for Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson, who had just announced that they had tested positive for covid. Maybe an hour or so before that announcement, the NBA season came to an end, after one of their players tested positive, too. At some point during the evening’s flurry of panic, Sarah Palin was revealed to be a contestant on The Masked Singer, and later that night, Donald Trump announced that all travel from Europe to the United States would be suspended for 30 days in an attempt to halt the spread of the coronavirus. The WHO declared a pandemic on March 11. The next day, I stockpiled the one thing that has gotten me through, and the next, I went to the grocery store and found chaos.

It is terrifically cliché to say this, but worth acknowledging anyway: Life changed a year ago, and it will never be the same again. Now that we have some distance, though, and have been living in what media outlets gingerly refer to as the new normal for a full calendar, I would like to call for an official moratorium on lifestyle instructionals about how to cope with uncertainty. We have all been living in uncertainty for an entire year. It is no longer the new normal, it is just life. Now’s the time to stop.

Because of this grim anniversary, media outlets have published big, long-winded oral histories of the day the world changed, rehashing in minute detail the wild ride that was March 11 of last year. The intentions behind this impulse are good; it has indeed been a long year, and remembering what happened yesterday is now a struggle, so it’s nice to have some perspective. The New York Times is commemorating this grim anniversary with a week’s worth of content from its occasionally-problematic Opinions desk, with an essay about nostalgia from Leslie Jamison, an oral history of 27 Americans’ last normal day, and, curiously, a diatribe against New Yorkers who left the city during the early days of this shit and are now returning, written like a bad Shouts & Murmurs column, that, unfortunately, has nearly broken my will to live.

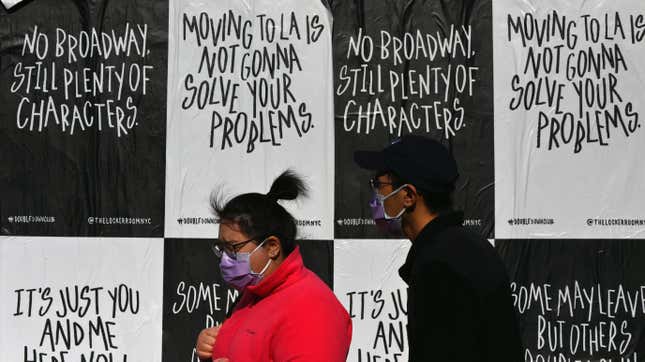

The piece itself is similar in tone to so many of the other pieces that have come out over the past year, and slots neatly into the newly-created canon of pandemic explainers, purporting to soothe the anxieties of the upper and middle-class who have been working from home for a year. In it, writer Luke Winkie addresses the people who left New York in the early stages of the pandemic, decamping for second homes or cabins upstate, while the rest of us stayed here amidst sirens and the 7 p.m. clapping, ducking into grocery stores and returning to our hovels to stew in our own anxiety.

The people that Winkie addresses are those who left to go to Joshua Tree, I guess, or other far-flung locales, in an attempt to escape what would inevitably come for them anyway, as if they were abandoning New York during its time of need instead of sticking it out in a city that was, as Winkie seems to think, a war zone. I recognize that this is an attempt at humor, but I have reached capacity for this sort of satire. No one deserves a prize or punishment for making personal decisions born of panic or fear, because in March 2020, no one knew anything about anything that was happening. That’s less of an excuse than an actual fact. We did not know then what we know now.

From the Times:

“It’s strange to watch those same friends, acquaintances and colleagues who abandoned ship orbit back to the city. We see them returning to those same tiny Brooklyn apartments as if nobody noticed their calendar-length disappearance — as if we did not witness the taunting patio cookouts that filled their paper trail while we spent 365 consecutive days counting the dots in the ceiling. I believe I speak for all pandemic-weathered New York City residents when I say that we cannot let these transplants off so easy. This indiscretion shall not stand.”

While I agree that at the time, there was something very annoying about watching people on Instagram traipse off to undisclosed locations to wait out what they thought would be just two weeks of bad times, which quickly ballooned into months and then, I suppose, a year, nothing about it now at this moment in time is irritating enough to inspire an op-ed in the Times. We’re also finally past the point of explainers that purport to tell an audience looking for confirmation that the way they are feeling is normal and fine, or, even worse, step in to fill the role of scold simply because the government was doing such a bad job in the first place.

What the explainers tried to do was assume that one person’s experience was universal, without taking into consideration the needs of the individual making the decisions for themselves. The second most harrowing part of the past year, after the death and the abject failure of the government to protect the people it serves, was the mental calculus required for every decision, weighing out the pros and cons of choices that felt risky, and then deciding to do whatever, anyway. No matter how many times an article on the internet said you shouldn’t go to the drugstore just to feel something other than dread, I still did it, anyway. That risk was mine to take, and so, I did. By now, we are all so used to these minute risk calculations that they are second nature. Being lectured about whether or not it’s safe to do anything is pointless, so why bother?

The lack of guidance over the past year about what is or isn’t the right thing to do left the decision of what was right up to the individual. This is a nightmare scenario that opened the door for content that is spiritually similar to Winkie’s piece, instructing the reader against things like sitting outside in the park with your friends but not appearing to be six feet apart from said friends in a picture on Instagram. Everyone was always going to make the choices that they did, and no amount of scolding from faceless writers on the internet was going to change that. But, now that there is a tentative light at the end of this hellacious tunnel, maybe it is in everyone’s best interest that we continue to keep our feelings to ourselves.