Two weeks into May, on a record-breaking 91-degree day, a handful of men and women gathered in a windowless conference room in a Planned Parenthood center in lower Manhattan; they were there to learn about a little-known state abortion law that forces women in New York to give birth to babies who will die in their first moments of life. The meeting was led not by a representative of Planned Parenthood, but by Erika Christensen, 36, and her husband Garin Marschall, 39, self-identified “amateur activists” who are unrecognizable by name or face but whose story has been read by more than 2.4 million people.

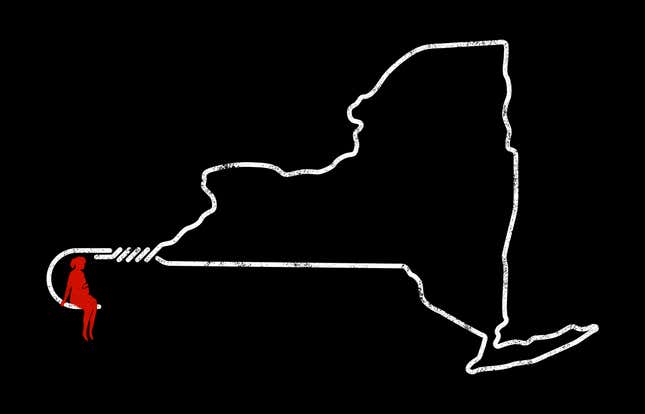

Last year, when she was 31 weeks pregnant, Christensen learned that the baby boy inside her had stopped developing and would die nearly instantly upon birth, choking for air. Due to a previous brain injury, the force of a vaginal delivery could kill her, so doctors would have to perform a C-section if she brought the baby to term. The doctors recommended an abortion, but because of a New York state law that prohibits doctors from terminating a pregnancy after 24 weeks—except in instances where the mother’s life is in immediate danger—Christensen had to travel out-of-state for the procedure.

At eight months pregnant, a few days after Mother’s Day 2016, Christensen and Marschall flew to Colorado. If TSA agents told her it wasn’t safe for her to fly, Christensen had been advised to tell them she was six months pregnant with twins. The couple borrowed money from family and spent $10,000 out-of-pocket for a procedure that can cost up to $25,000. Christensen shared her experience to Jezebel anonymously in a powerful interview with then-editor Jia Tolentino that attracted the attention of state legislators, activists, and women across the country who have shared the same burden.

In an op-ed recently published in Rewire, Christensen wrote, “I lay on the table, looking up at the ceiling. My internal questions played like a tape over and over in my mind: Why am I here? Did New York expect me to carry this baby to term, only to watch him suffer and die? Since then, I’ve tried to answer that second question. The only answer I’ve come up with is: yes.” Despite this, Christensen considers herself lucky—at least she could afford to go through with the out-of-state procedure. Low-income women are forced to birth babies that will die immediately, or will fight to live every day of their short lives.

One year later, the couple has chosen to put themselves at the forefront of the fight to reform the law that forced them to flee the state like criminals. “I don’t think any of us are really thrilled to put ourselves out there like this,” Christensen said to the dozen or so people in attendance. “But we’re now more angry than we are sad.”

“Nobody knows about this, nobody cares about it,” said Marschall, as he led the group through a PowerPoint presentation about New York’s current abortion law. “There’s a big groundswell of support for progressive causes after the election. This is not on the radar, it’s not on the map at all.”

The New York state senate is scheduled to end its session on June 21. If it ends without passing a reform, another round of New York women will be forced to endure the traumas that Christensen did. “Yes there are huge problems, yes Trump is literally driving the country over a cliff,” Marschall said at the meeting, “but this we can affect, and it could help people. And it could help people this year if it were able to pass.”

New York’s Abortion Law

There’s a common misconception that New York, a bastion of progressive politics, is a safe haven for abortion rights. “Many, many New Yorkers, legislators, and people on the street just assume New York state has good reproductive health laws because we’re a progressive blue state,” said New York State Sen. Liz Krueger in a phone interview with Jezebel days after the meeting at the Planned Parenthood clinic. “While we were the first in the country, the law we passed, by modern standards, was pretty lousy law.”

Early-term abortions were legal under common law in America until the 1800s, when anti-abortion physicians sought to increase birth rates among white, Protestant women and to maintain their power in the medical establishment as it opened up to women. New York criminalized abortions in 1828, entering an “abortional act” into its penal code, alongside homicide and manslaughter.

Except in instances where it was deemed necessary to save the mother’s life, abortion remained a punishable crime through the 1960s. But as public pressure from activists and feminists grew, in 1968 New York’s Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller asked a commission to review the abortion ban. When a reform bill came to a vote in the General Assembly on April 9, 1970, New York’s lawmakers were split on the issue.

Assemblyman George Michaels, a pro-choice Democrat who represented a rural, conservative county in the Finger Lakes region, took to the podium during the vote with his “hands trembling,” according to the New York Times. “I realize, Mr. Speaker, that I am terminating my political career, but I cannot in good conscience sit here and allow my vote to be the one that defeats this bill,” said Michaels. “I ask that my vote be changed from ‘no’ to ‘yes.’” Michaels’s vote did indeed end his decade-long political career, but it paved the way for legal abortion access, turning New York into the first state to legally provide abortions to both out-of-state and in-state residents.

The New York state law that Michaels helped pass, which stands today, revised the penal code to create an exception for a “justifiable abortion” as one that a doctor provides within 24 weeks of a woman’s pregnancy or in instances when the woman’s life is at risk. For three years, New York was the nation’s leader on abortion rights. Then, with the passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973, abortion became a constitutional right, rendering the state law moot—or so it seemed.

The state law technically makes providing an abortion after 24 weeks a Class D felony, punishable by up to two to seven years in prison, and makes self-induced abortions a misdemeanor crime. By specifying “duly licensed physicians,” the law also deters certified midwives, nurse practitioners and physician’s assistants from providing first-term abortions, even though they are qualified to do so and play a big part in increasing access to early care. “There’s a direct conflict between New York state law and constitutional law,” said Katharine Bodde, policy counsel at the New York Civil Liberties Union. “That means that women like Erika are being sent out of state if they can afford to go out of state, or are being forced to carry a doomed pregnancy to term,” she said. “Which is pretty cruel.”

According to the Guttmacher Institute, only seven states— California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, and Washington—have laws consistent with Roe v. Wade. New York is unique because, out of the four states that legalized abortion pre-Roe v. Wade, it’s the only state that hasn’t revised the law.

The penal code also criminalizes self-induced abortions. “Having a law that directly criminalizes self-induced abortion is extremely rare. Only seven states have such laws,” said Farah Diaz-Tello, an attorney with the Self-Induced Abortion Legal Team. “These are mostly hold-over laws from Roe.” However, the state rarely prosecutes women for self-induced abortions because it’s difficult to prove what ended a pregnancy (the last arrest for self-induced abortion that Diaz-Tello recalls happened in 2011, but the Manhattan district attorney dropped the case over lack of evidence). “If Purvi Patel had been in New York, she also would have been criminally prosecuted,” she said, referring to the Indiana woman who was convicted of feticide after self-inducing an abortion in 2013 (though, Diaz-Tello notes, the degree of the crime would have been different in New York). This a problem that New York is “long overdue in addressing,” she said.

In theory, constitutional law supersedes New York state law, and in 2016, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman declared that “New York’s criminal law cannot penalize reproductive health decisions protected by the U.S. Constitution.” However, even with Schneiderman’s assurance, risk-averse hospitals adhere to state law and reserve the right to terminate hospital privileges or fire doctors doctors who violate it, said Dr. Stephen Chasen, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Weill Cornell Medical College and maternal fetal specialist who takes care of high-risk pregnancies like Christensen’s. Chasen has been championing abortion rights in New York since he offered expert testimony challenging the partial birth abortion ban in New York in 2004. While a hospital might provide special, case-by-case approval to perform a late-term abortion, the process can be too lengthy when a woman’s health is deteriorating. The gap between the state law and the federal law is “a black line, it’s not a gray zone,” he said.

About two-thirds of abortions take place in the first trimester of pregnancy, and nearly 99 percent happen before the 20th week. According to the the Guttmacher Institute, it’s unclear how many of the 1.3 percent of abortions that happen after 20 weeks are due to health risks or fetal abnormalities that arise late in the pregnancy, but a majority of women receiving late-term abortions learn about their pregnancies late and face more hurdles in accessing abortion than women who receive them in the first trimester. Studies have found that 47 to 95 percent of women may chose to terminate their pregnancies after a major genetic of fetal anamoly is detected in the second trimester (demographic differences between the populations studied likely account for the wide range).

“If you’re talking about an uncomplicated pregnancy, 24 weeks might be a reasonable place to draw the viability line and say that in general, a baby born alive after 24 weeks with aggressive neonatal care has a good chance of survival,” said Chasen. “But in a complicated pregnancy, that might not be true.” Chasen adds, too, that a fetus can survive in utero with a lethal fetal abnormality—like a fetus without a kidney or a heart—but cannot survive beyond the womb, or survive with a reasonable quality of life.

In some cases, delaying the removal of the fetus in a complicated pregnancy can also cause health problems for the mother. For example, if a woman breaks her water in the second trimester before there’s amniotic water around the fetus, the fetal lungs will not develop. The woman might stay pregnant with a fetal heartbeat, but every day that a woman stays pregnant, she’s at risk of getting a bacterial infection of the blood called sepsis, which increases the risk of her health, Chasen explains. But the state law prohibits Chasen from terminating the pregnancy until he determines that his patient is lying at death’s doorstep, which is hard to predict. “A woman can go from her health being at risk to her life being at risk very quickly,” he said, comparing it to walking towards the edge of a cliff. “You don’t know when you’re over the cliff until you’re over the cliff.” Chasen says that New York’s state law directly impedes his ability to provide urgent and critical care to his patients. “It makes no sense. It goes against everything you think you are as a physician,” he said.

There are no statistics on how many women require abortions due to complicated pregnancies in New York. But it’s uncommon for Chasen to go more than a few months without seeing patients with severe fetal abnormalities like Christensen’s. “Being an abortion provider is not a separate thing from maternal fetal medicine specialist,” he said. “A general surgeon doesn’t have to lobby to be able to take out a gall bladder the way he or she thinks it’s safest and when he or she thinks it’s safest to do.”

The Reproductive Health Act

The solution exists in The Reproductive Health Act, which would bring the state’s abortion law up to date with Roe v. Wade. First, it would decriminalize abortion (including self-induced abortion) by moving it to New York’s health code. It would also permit licensed abortion providers to terminate pregnancies after 24 weeks when deemed medically necessary. “The Reproductive Health Act would help us act on behalf of the woman’s health,” Chasen said.

The bill traces its origins back to former Gov. Eliot Spitzer, and has since gone through multiple revisions that have stalled in the state legislature. The latest version of the RHA, cosponsored by Krueger and Democratic Conference Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, passed the Assembly in January. It now sits at the footsteps of the Republican-controlled senate. Krueger, who witnessed Republicans sweep the midterm election and ramp up their assault on reproductive rights in 2010, assembled the New York State Bi-Partisan Pro-Choice Legislative Caucus to educate lawmakers about abortion rights and choke support for anti-choice bills as they were drafted. “I decided that in New York, we needed to play offense rather than waiting around to play defense,” she said. “I’m proud to say that in a country where even blue states have been passing anti-choice bills over the last six years, none of those have made any traction or moved in the New York State legislature.”

But with the election of Donald Trump and a Republican-majority Congress, there’s a new sense of urgency to pass reform—and more at stake if it fails. “In the era of Trump, Roe v. Wade could be overturned,” she said. What Krueger envisions as a likelier scenario, however, is that Republicans will “go statehouse by statehouse” and “pass terrible bills that cut away at protections of Roe v. Wade”—even more aggressively than they’ve been doing since 2010. If those laws are challenged and win in the court, they will be the new precedent, she says, “that technically supersede Roe v. Wade.”

“At that time, after the first one hits and we lose, even saying Roe v. Wade at a state level is a moot point. And then all we’ll be left with, in New York state, is this 1970 statute that in certain circumstances, your doctor isn’t going to go to jail for performing abortions,” she said. “That’s not a reproductive health law.

“I think it’s really important for people to understand that we have a lot of smoke and mirrors instead of a solid statute,” she continued. “And you can go to red states statutes in the country and find far better laws on their books than you can in New York.”

Effect On Women

Planned Parenthood, the National Institute for Reproductive Health, and the NYCLU are among several organizations that have been lobbying for the RHA for years, with little success. “One of the things we kept hearing in the senate over and over again was, ‘Show me a woman who can’t get an abortion in New York state,’” said Bodde, adding that the response “clearly demonstrated that there was a willful lack of understanding between what was happening on the ground and our policy makers.”

The NYCLU has been gathering stories of women and girls affected by the law for years: In one tragic case, a 12-year-old girl was sexually assaulted. Her parents did not learn that she was pregnant until she was at 26 weeks—past the state limit to receive an abortion, which makes no exceptions for rape or incest. “She was a tiny girl with anemia, and she faced health risks if she were forced to carry her pregnancy to term and deliver vaginally,” the report notes. “But a C-section would also be a health risk. It would likely weaken her uterus and jeopardize her ability to have children later in life. Termination was the best course, but now it wasn’t available to her in New York.”

Another woman discovered that the fetus had polycystic kidney disease at 20 weeks. Further testing was required, but then Hurricane Sandy struck and shut down the hospital. By the time doctors confirmed that the fetus was incompatible with life, it was too late for her to get an abortion in New York state. Unable to afford to travel and pay for the procedure, she was forced to deliver a still birth, further jeopardizing her health. During delivery, she suffered a hemorrhage that could have killed her. Thankfully, she survived.

“We collected these stories, and it’s certainly really difficult—there are so many reasons why a woman wouldn’t want to have her story published, and we ran into that a lot,” said Bodde. But then, through the Jezebel interview, Bodde found Christensen and Marschall. “I can go into an office and I can talk until I’m blue in the face, but it changes it so much when a woman like Erika and her husband Garin walk into a room and share their story,” she said. “There have been several moments where legislators have actually gotten emotional because of Erika and Garin sharing their story.”

New York’s senate is in session between January and June, with a focus on the budget for the first three months. This schedule gives activists just three months to aggressively lobby lawmakers and pressure them to bring the RHA to a vote. Christensen, Marshall, Bodde, and others are turning up the heat. The couple recently launched a social media campaign and website to raise awareness about the RHA. The NYCLU has circulated a petition. Christensen has rounded up stories from other women and presented them to senators.

In one such story, Moira*, 36, did not realize her pregnancy was at risk until an ultrasound revealed that her baby boy’s brain had stopped growing and was filled with fluid at 26 weeks. “I’ve always considered myself pro-choice, but to be honest, there was a part of me that, for all my adult life, thought that by the time you’d be at 26 weeks you’d know if something was wrong,” she told Jezebel. “I thought that a late-term abortion was for someone who hasn’t been paying attention, and now I know that’s not true.”

The prognosis was microcephaly and hydrocephalus—traumatic brain injuries that, according to doctors, would leave her son with severe disabilities. Moira was told her baby would be “lucky” to live beyond five years old. Doctors advised an abortion, but by law, Moira couldn’t receive one in New York. So at the 28th week of her pregnancy, Moira and her husband flew to Albuquerque, New Mexico, for the procedure. “It feels like a you’re a criminal. Like you’re doing something outside the law,” she said. The flight, rental car, hotel stay, and procedure cost the couple about $12,000. None of it was covered by insurance.

“My moral compass says that that’s not right and that I had to take this pain and sadness so that my son wouldn’t have to live trapped in a broken body,” Moira said. “I challenge any of those people in Albany who are making this law to sit in the room with me where I sat with my dead son and face that.”

Lobbying Senators

Christensen and Marschall have visited Albany three times in the past several months and said that while some senators were moved by their stories, others were skeptical of the proposed reform. “Might I recommend, for therapy, if something traumatic has happened to you, say it out loud to people 300 times. And then it actually starts to lose a lot of its power!” Christensen joked.

She recalled that one Republican senator’s aide told her, “‘We can’t support this bill because they said podiatrists would be giving abortions.’ This is what we’re dealing with,” she said. “Literally, another one said to us: so she could just get an abortion for a headache at 30 weeks?” She was told that including the provision for “health of the woman”is “too broad.” And last year, Republican Assemblyman Ron Castorina referred to abortion as “African-American genocide.”

But Krueger and her caucus have been working to educate senators, particularly Republicans, about the benefits of the bill. “It’s really important for people to understand lots and lots of folks—including legislators—have questions they don’t understand. And they’re not sure who to go to to ask because they’re the ones who are supposed to know,” she said.

Through these off-the-record conservations, she believes that the bill has the support it needs to pass into law. “I believe there are multiple Republicans who may not go on the bill as co-sponsors, but if it comes to a vote on the floor, will in fact vote for the bill. But we’ve get to get it to the floor,” she said.

This point is crucial: the bill cannot reach a vote if it’s not brought to the floor. And that decision lies with the Health Committee, chaired by Republican State Sen. Kemp Hannon, or Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan. An aide in Krueger’s office said that Flanagan does not support the Reproductive Health Act, and though Kemp has not publicly commented on the bill, it’s unlikely he would support it. (Flanagan’s office did not respond to Jezebel’s requests for comment.)

When Christensen and Marschall met with Hannon in April, they described him as “obstinate” and “not interested our story at all.” He made it very clear that “he would not support this bill,” Christensen said.

So with time running out, what’s the next move? “To get a vote on the RHA this session would take the Governor using his skills and political muscle to pressure Sen. Flanagan to bring the bill to the floor,” Krueger said via email. She’s referencing Governor Andrew Cuomo, who has shown support for the bill. In January, Cuomo announced that his administration was proposing an amendment to New York’s constitution that would expand abortion and contraception coverage, requiring health insurers to cover medically necessary abortions and “codifying the protections established by the 1973 Roe v. Wade into the state constitution.” However, an amendment could take years longer to put in place than simply passing the RHA in the next month.

Turning to Activism

After Christensen terminated her pregnancy last year, she left her corporate job and the couple moved from Brooklyn to a smaller city in another state to focus on recovering. They found a fixer-upper and spent six months putting up drywall, sanding and painting walls, and rebuilding a staircase. Then, at the end of August, Christensen had what she thought was her third pregnancy, and second miscarriage, in two years.

She was shopping at Whole Foods when the blood came rushing, soaking her like she was in “a total crime scene.” Marschall left her in the bathroom and ran out to get her new clothes. Worried about her fertility, they made an appointment with a specialist. That’s when they learned that Christensen was four months pregnant. The incident at Whole Foods, doctors said, was most likely a miscarriage of a twin.

“After I found out that I was pregnant, we started to refer to the baby as Furiosa because she was so ferocious in there and we were cooking her pretty much entirely on rage and disappointment,” Christensen said. “Now she’s just this loveable, adorable little baby.”

“Every time we went to the doctor, we were terrified,” she said. Doctors used the word “perfect,” Christensen could feel the baby kicking and moving, and all of the ultrasounds were normal. “We’d feel momentarily relieved, and then the cycle would start again, where we’d feel okay for a few days, and then we’d see the next appointment coming, and then we’d get nervous again.”

“We were braced the whole time,” she said. “I’m still in denial that we have a healthy baby.”

Christensen was nine months pregnant when the NYCLU invited her and Marschall to lobby with them in Albany in March. The couple accepted without hesitation. Racing against a blizzard, they drove seven hours north to the statehouse to meet with lawmakers and activists and delivered their first public speech about the abortion in front of hundreds of people in near-freezing temperatures. They made the 14-hour round trip twice more in the months that followed—once with their four-week-old infant in tow.

Through an online support group, Christensen continues to hear from women like Moira. “Now I know that this is a thing, I feel that this happens on my watch,” she said. Their suffering, along with the birth of her daughter, has helped her stay engaged with activism full-time. “I think to us, working on this stuff is focusing on her. She’s a girl. I don’t want [my daughter] to have to be schlepping to Albany, doing this work for us in 18 years.”

*This individual’s name has been changed.